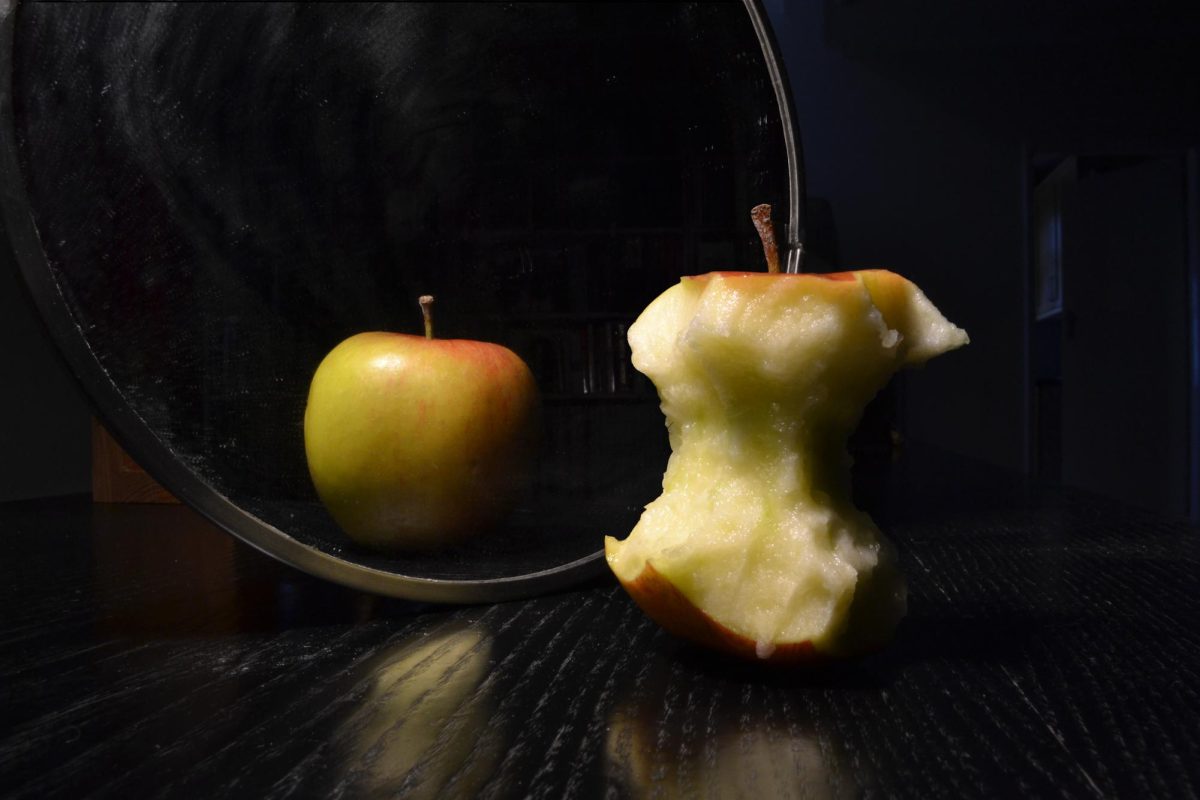

Having the “ideal” body is broadcasted to consumers in all aspects of media, especially through social media platforms. Posts state that being fat is wrong, that it’s easy not to be fat and that skinny people are more attractive. Often when an overweight person states that they are fat, they get the response, “No, you’re beautiful!” insinuating that fat and beautiful are opposites.

For the past several decades, the ideal body consists of having the perfect proportions, encompassed by the term “hourglass figure.” This figure consists of a wide bust, a narrow waist, wide hips and, most importantly, being skinny. Having an hourglass figure is largely determined by genetics. However, society has made the hourglass figure seem like the only acceptable and desirable body shape.

This idea of a perfect body incentivizes consumers to purchase products that are rumored to help with weight loss to obtain that ideal when in reality those products are catered to combat health conditions. For example, drugs for Type 2 diabetes such as Ozempic and Wegovy, are being misused as a way to lose weight without being prescribed. This can lead to mild consequences such as nausea, stomach pain, and vomiting, or more serious consequences like kidney failure and cancer.

The idea of having a perfect body can push people away from certain nutrients, such as fats and carbohydrates, which are two macronutrients that are wrongly demonized as a major reason for weight gain. These myths regarding dieting and losing weight, as well as this social norm that thinness equates to being healthy, are dubbed “diet culture” and can lead to drastic consequences. These consequences manifest as eating disorders, fatphobia and institutional inequalities like seatbelts not protecting fat people as efficiently as they protect skinnier people.

Diet culture is extremely prevalent, and even though 95% of diets targeting weight loss don’t work, around 45 million people go on a diet each year. This subsequently benefits the diet industry which makes over $60 billion a year, despite their products having a long history of being unsuccessful in long-term weight loss. The industry has no reason to remedy this, as the profit they make exceeds the small criticism they receive.

People who go on diets are eight times more likely to develop an eating disorder such as anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa, according to Courage to Nourish. Now take into consideration that 46% of nine to 11-year-olds are or have been on a diet. These kids are at risk of eating disorders. Eating disorders are widespread, with 28.8 million Americans having an eating disorder in their life, and one person every 52 minutes dying of an eating disorder such as anorexia.

Diet culture is not only predominant in society due to companies pushing for weight loss tools or social media; we give power to diet culture through simple things such as our everyday vocabulary. For example, the derogatory usage of the word “fat.” Saying your friend is fat for eating a bag of chips and getting a drink, because they don’t engage in as much physical activity as you do, or simply because of the shape of their body.

Historically, the word “fat” has been used in many different ways. In the late 14th century it meant “abundant,” and in the 17th century, it was used as a synonym for affluence due to the many famines that caused food shortages. Being what today is defined as overweight was an expression of wealth, signifying access to abundant food resources. In the past, there has been an underlying positive connotation for the word fat. Our society hasn’t always been as harsh on larger bodies as it is now.

However, in the 1830s, the meaning transitioned into something much more negative. A century later, the term “fatso” emerged. By the 1940s, thinness became the new ideal body type. People now associate fatness with gluttony. The ever-opportunistic diet industry took advantage of this new mindset to increase profit.

And profit they did. According to the Colorado State University Kendall Reagan Nutrition Center, the diet industry is one of the most profitable in the world, with a net worth of $72 billion in the U.S. alone. As individuals, it is challenging to combat an ongoing industry. However, a good way to begin would be to limit how much we feed into it, such as by not using the word “fat” negatively.

It may seem like a small comment or a joking insult, but its effects are incredibly significant. Research shows that the weight discrimination the media pushes onto us can manifest as early as four years old when kids on the playground state they don’t want to be friends with an overweight child. Four years old and they already have hate in their hearts.

When we use “fat” as an insult, we completely disregard the scientific truth: someone’s weight is a result of many complex factors, the majority of which are out of a person’s control. We do not always know what’s going on in someone’s life, so what gives us the right to pass judgment on others for their weight?

The word fat carries negative connotations, which come with deeper consequences, like internal bias. Firstly, this can manifest itself in fatphobia, the “pathological fear of fatness.” Externally, fatphobia manifests in insults and derogatory uses of words like “fat” along with an extreme phobia of becoming overweight. Internally, it can be as small as an automatic assumption that someone who is overweight cannot be fit, which also happens to be scientifically inaccurate.

A second consequence of fatphobia and diet culture can be mental disorders such as body dysmorphic disorder (BDD), more commonly recognized as body dysmorphia. With more than 200,000 yearly cases in the U.S., body dysmorphia is incredibly common and occurs when someone obsesses over a perceived flaw in their appearance. Derogatory uses of words like “fat” can worsen and sometimes even cause conditions such as these.

When we fat-shame and perpetuate weight stigmatization, we can harm people’s mental health and encourage them to damage their physical health, which can lead to eating disorders such as anorexia. As many as 43% of people with anorexia reported suicidal ideation, and as many as 20% attempted suicide.

This is no longer a funny joke. This is real people’s lives. We might think it’s alright to jokingly use the word “fat” with our friends, but it’s impossible to know how someone truly feels. And, even if your friends do not get harmed by the word, those overhearing may be injured.

The word “fat” is not to be removed entirely from our vocabulary, it’s just to be reevaluated. It’s not a bad word and shouldn’t be used as such. Using it negatively simply reinforces the harsh culture of judgment we live in and can contribute to catastrophic consequences for others.

We don’t know what is going on in others’ minds. Dysmorphia can be silent. Eating disorders can be silent; the effects of diet culture and our participation in it are not always abundantly clear.

Calling your friend “fat” as they take a bite of their favorite muffin may just trigger a response within them. Don’t be the reason they are scared to take another bite.

By Mahina Diaz-Asper and Jeremy Loko