The Israel-Palestine conflict. The war in Ukraine. Confrontation in Taiwan. The civil war in Myanmar. These are only some examples of conflicts around the world that have been labeled as “worsening” by the Council on Foreign Relations’ Global Conflict Tracker. My question is, why are we not talking about these events at WIS? Or at least, why do students not have the forum to do so?

Arguably, the most prevalent global conflict that has engaged universities and colleges in discussion recently is the Israeli-Palestine conflict. The conflict has a long and tumultuous history, dating back to the early 1900s with thousands of people dying along the way. With the October 7th Hamas attack on Israel sparking a newfound wave of violence, thousands of student protests emerged in university and school campuses throughout the world.

In response, most educational organizations faced two choices: to either remain silent or to open the table to discussion. Remaining silent would not stop student voices, but it could allow for anti-Semitic or anti-Palestinian rhetoric to arise, potentially causing students to feel unsafe or unsupported by their schools. Such events occurred at Harvard University, the University of Pennsylvani, and MIT.

However, opening up the table to the discussion could allow students with opposing viewpoints to have a conversation and express their emotions and their opinions. Just because a topic is controversial does not mean two people on opposing sides can not listen to each other peacefully. Is that not what diplomacy is?

Universities such as Princeton and Columbia have started opening up discussion forums, allowing their students to witness the impact of these conversations. Dean of Princeton’s School of Public and International Affairs (SPIA) Amaney Jamal and Dean of Columbia’s School of International and Public Affairs Keren Yarhi-Milo spoke at SPIA about the importance of having these tense conversations.

“I love seeing students caring about what is happening,” Yarhi-Milo said at the event. “The worst thing is political apathy. We can have difficult conversations. We might disagree, but we might learn a lot from one another.” Not only do leading political scientists have these discussions, but they encourage students to do so as well.

Both Jamal and Yarhi-Milo wrote an op-ed for the New York Times about the importance of encouraging these discussions in school environments, citing tools such as webinars and featuring diverse voices at school as methods to spark and create discussion. While they approach the article from an undergraduate and research university perspective, these ideas are still applicable to WIS.

Through the Rose Castle Foundation, Princeton teaches students from different backgrounds, faith traditions and political orientations how students with opposing viewpoints can come together. While WIS is not an undergraduate institution and thus has different resources, we should follow the example of leading institutions, by having more discussions and awareness of these issues.

In universities and high schools, these discussions are crucial. “[F]orums like formal classroom debates and moderated panel discussions are vital to promoting healthy discussions,” President and CEO of the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE) Greg Lukianoff said in an ABC News article.

While the discussions above all focused on the Israel-Palestine conflict, it is not the only time a global crisis has occurred and WIS has remained silent. The Russia-Ukraine war, while arguably much less of a divisive topic, was also met with silence from the WIS community, students, teachers, and administration alike. Students should at least be provided with information and news about the events in Russia and Ukraine, including their historical context either from the administration or through different clubs and forums.

Following the Russian invasion, colleges and universities across the U.S. responded with student and institutional acts. Student demonstrations and fundraising campaigns organized by students and universities for Ukraine are some examples of what schools did according to an Insight Into Diversity article.

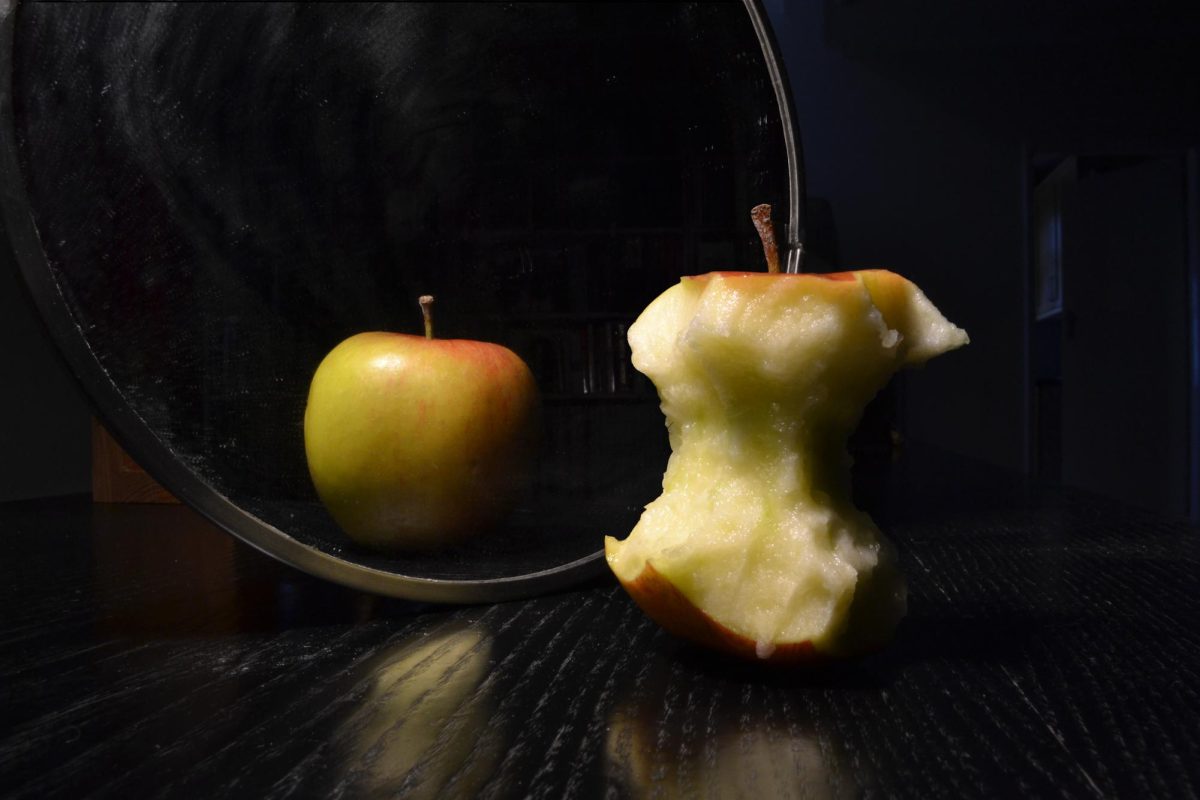

Yes, at times the news can be demoralizing. Opening Apple News, or even a paper newspaper from the New York Times can often lead to feelings of depression and resignation as nothing seems to be improving. However, for those following the news, especially if their country is involved in a conflict or if they have friends or family in such situations, providing a space for these discussions is crucial, and as a school, we should encourage them.

“The war in the Middle East, race, abortion, COVID—students and faculty tell us these are topics they are uncomfortable discussing on many campuses because they’re so heated. But they’re the most important issues of the day,” an attorney with the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression Alex Morey said in an Inside Higher Ed article. These topics and conversations are not going away any time soon, and we need to begin becoming more comfortable discussing them.

Being an IB school focused on global-mindedness, awareness and internationalism, should come with an emphasis on understanding what is happening in the world. Maybe this can be addressed through a Global Politics club, which sits down and discusses these issues and allows students to have a debate in a safe space.

Presentations at assemblies from a Global Politics club could also make the news digestible and feed important pieces of information to the general student body. Perhaps this change comes in the form of quick links on the Devil’s Details or announcements in advisory. This change is not drastic to implement, but it is critical to do.

For a school that emphasizes the idea of being a global citizen, we need to make sure that many of us are aware and able to discuss what is happening outside our borders. I am not saying let us all become experts in every global conflict. I am saying to at least open up the forum for discussions in these conflicts, or awareness on what is occurring. Discussions are powerful- let’s start creating them.

By Elektra Gea-Sereti