Sophomore Bianca Pattison is online thrifting for sweaters. Not just any sweaters, vintage sweaters. She says she needs clothes to stay warm for the winter. After scrolling for a while, her cursor finally stops on a blue crewneck. It has cats and birds embroidered on it. She realizes it’s stained and moves on.

Pattison is one of the 40 percent of Generation Z that shop second-hand, according to a 2020 Resale Report from ThredUp, an American online thrift store.

ThredUp cites sustainability and affordability as the main reasons for the recent increase in teenage thrifting, compared to 2016.

WIS high school students agree.

“There are more options at thrift stores than what there are in retail stores and because it’s way cheaper and there are vintage clothes,” sophomore Emma Gutnikoff said.

Students also cited sustainability as a reason for thrifting.

Senior Sophia Nehme explains that buying clothes second-hand decreases clothing waste in landfills and limits the amount of methane and CO₂ in the atmosphere from clothing production which helps counteract man-made climate change.

Sophomore Sabine Thomas thrifts to avoid shopping at fast fashion brands. Fast fashion is “an approach to the design, creation, and marketing of clothing fashions that emphasizes making fashion trends quickly and cheaply available to consumers” according to Merriam-Webster.

While fast fashion is a profitable strategy for clothing companies, it results in extreme amounts of clothing waste as trends go out of style quickly and brands overproduce. “The fashion industry is responsible for 10 percent of annual global carbon emissions, more than all international flights and maritime shipping combined,” according to the World Bank.

Thomas thrifts for specific items to combat wasteful fashion. “Because clothes like jeans are so hard on the environment and release so much carbon, I try to buy pants thrifted or from sustainable brands,” she said.

“A single pair of jeans, on average, emits 34 [kilograms] of CO₂ to be produced, similar to taking a car and driving for 111 [kilometers],” according to the Fashion Revolution.

Fast-fashion has ethical concerns as well. “Many workers in factories of fast fashion brands are often underpaid/forced to work in grueling conditions,” Nehme explained.

Fashion Nova is a fast fashion company that got exposed for underpaying it’s employees in 2019 by the New York Times.

“The [United States Labor Department’s wage and hour division] discovered Fashion Nova clothing being made in dozens of factories that owed $3.8 million in back wages to hundreds of workers,” according to the New York Times. “Those factories, which are hired by middlemen to produce garments for fashion brands, paid their sewers as little as $2.77 an hour.”

Fashion Nova’s working conditions are just one example of fast fashion’s ethical costs.

Thus, thrifting has proved to be a sustainable option that allows teens to participate in anti-climate change and ethical activism while maintaining affordability.

However, as in-person thrift stores closed throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, thrifters resorted to reselling and buying second-hand clothes online, on apps such as Depop.

Depop is a peer-to-peer clothing app where consumers can buy directly from individual sellers. The app aims to “make fashion more inclusive, diverse and less wasteful.”

Thomas, Pattison, and Nehme all use Depop to shop second-hand.

Depop’s sellers price their own items, and while this allows for a certain degree of freedom, it may also produce clothing prices that are inaccessible for low-income families.

“Individuals often overprice thrifted items for the ‘look’ or ‘aesthetic’ of selling something second hand,” Nehme said. “I have seen people sell thrifted polos [or] T-shirts for upwards of $50 when it is apparent they were purchased at thrift stores for far less.”

Depop has a negative impact in terms of fast fashion as well. The price of thrifted clothing on the app may discourage customers from shopping secondhand.

The benefits of thrifting have created a cycle among the economically privileged. Customers thrift for ethical and environmental reasons and, as the demand for secondhand clothing increases, so do the prices. Nonetheless, these customers can afford to pay the new price, and thus the price continues to rise.

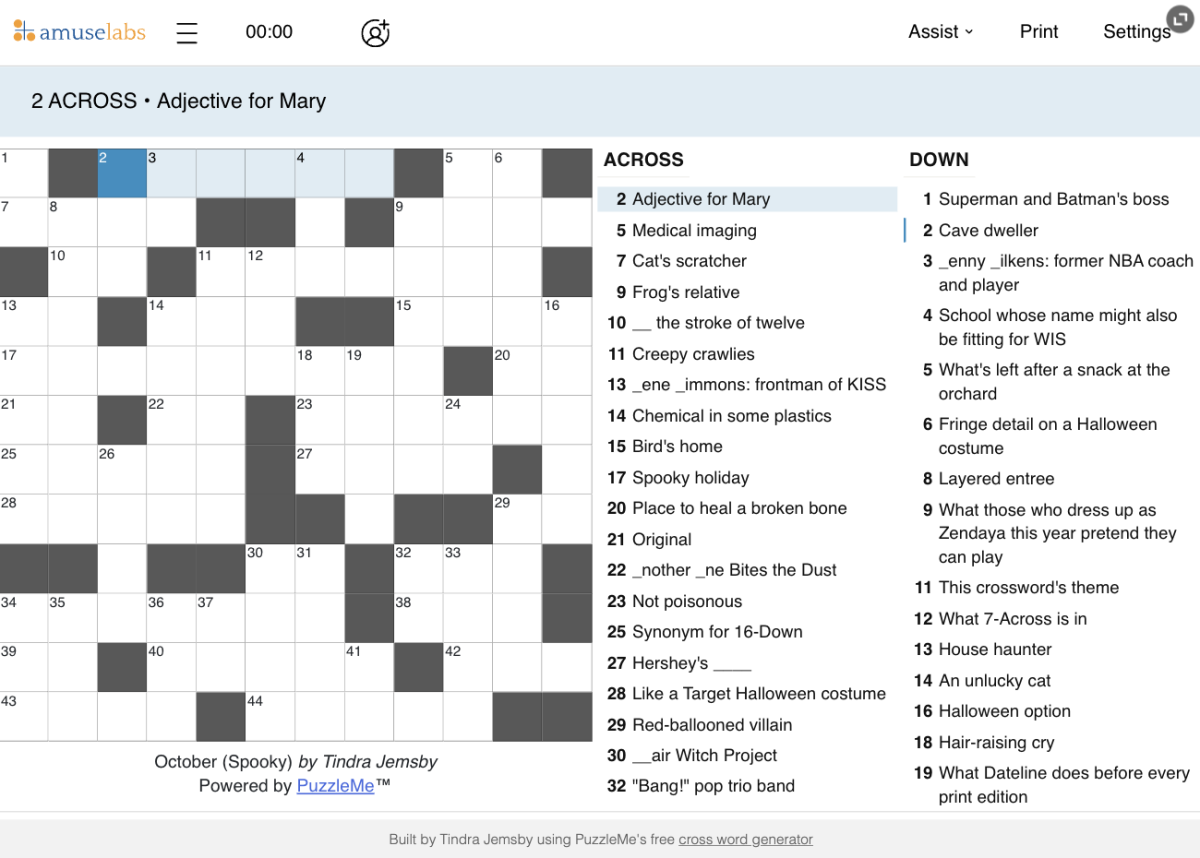

It is interesting to note that the demand for thrifted clothing has created a new retail format in recent years, vintage stores. Unlike thrift stores, vintage stores sell a curated collection of vintage clothing that draw a premium price. Thrifted, an online vintage store, prices it’s jackets and coats from $13 to $1,288.

Many vintage stores get their inventory from thrift stores, which can cause a scarcity of good quality items.

Nehme acknowledges the choice she makes to thrift and acts accordingly. “I stray away from buying winter coats, shoes, children’s clothing, furniture, books, etc…which there are less of than common clothes like T-shirts,” she said.

Additionally, to help prevent a shortage of clothing, Nehme uses her resources. “I also donate back to the thrift stores I shop at to ensure clothes are continuously cycled into the store,” she said.

The senior makes a final point. “I am privileged because I personally choose to shop second-hand and do not have to rely on it as the most accessible [or] economically feasible option for me.

By Abigail Bown