This article follows Dateline’s anonymous sources policy. Some interviewees’ names have been changed to protect anonymity.

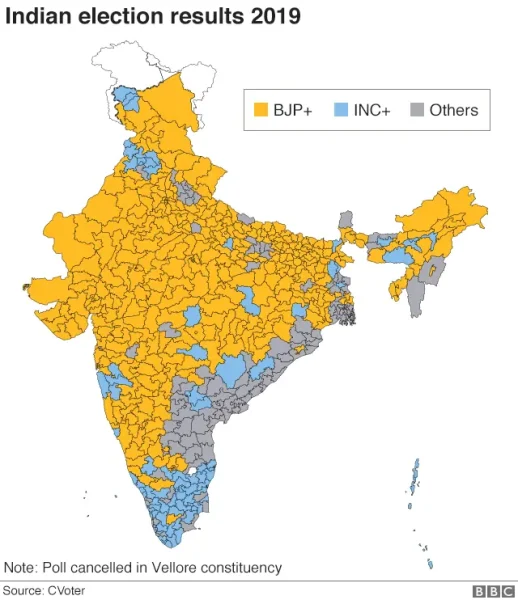

On April 19 2024, India’s electorate of 968 million will cast their vote in their country’s general election. The election will be a contest between two formidable adversaries, each part of larger coalitions: the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and the Indian National Congress (Congress or INC). The incumbent BJP, propelled by an agenda of economic reform and their populist leader, Narendra Modi, who has made Hindu nationalism the heart of his party’s appeal, is expected to win a third term in office.

Meanwhile, Congress, with its legacy of upholding secularism (the separation of religion and government) and promoting social welfare, aims for a resurgence on the political stage.

The BJP has dominated India’s political landscape since the 2014 general election, where they won a landslide, and have since then been seen as the party that delivers an improved standard of living for the majority.

Nevertheless, the BJP’s ties to the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), a right-wing, Hindu nationalist organization sometimes described as being a paramilitary group, have been brought into question. The BJP’s flagship ideology of Hindutva (literally: Hindu-ness) has been accused of emboldening Hindu vigilante groups like the RSS.

Due to the BJP’s success in passing legislation that appeals to the Hindu majority in India over the last decade, the main opposition party, Congress, has struggled to gain sufficient popular support since 2014 to form a government. Some say this is because of the BJP’s success in economic development that captured more of the rural and suburban vote, or the lack of a charismatic Congress leader to challenge Modi and win over India’s liberal voters.

The current leader of Congress, Rahul Gandhi, comes from India’s most famous political family, descended from India’s first Prime Minister, Jawaharlal Nehru. The INC had dominated Indian politics in the decades after independence, and now, Gandhi is faced with the task of leading his party, as well as the coalition of which Congress is a part of, in the fight against the dominant BJP. Gandhi’s Congress is accused of widespread nepotism, and many argue that Congress needs to turn over a new leaf if they truly want electoral success on a national level.

Siddharth Sivakumar, a student at North Carolina State University originally from Tamil Nadu, a south Indian state, believes that if Congress wants to survive and defeat Modi, they need someone more charismatic than Gandhi who can show that they have tackled the issue of nepotism in their party.

“I don’t think there’s any political party in a truly democratic nation, that has the key definition of nepotism [within them], that you can consider as being a good party to support,” Sivakumar said. “I think if the Congress Party truly wants to survive and give opposition to the BJP, they need a better leader.”

Gandhi was disqualified from the Lok Sabha, India’s lower house of Parliament, in March 2023, and was then convicted on charges of defaming Modi’s surname, charges he and his allies labeled as being politically motivated. While he spent some time in jail as a result, the conviction was recently overturned, and he is still eligible to run in the election this year.

In overturning Gandhi’s conviction, India’s Supreme Court noted that the two-year sentence given to Gandhi happened to be exactly the minimum required to disqualify a candidate from holding public office. Indian defamation cases rarely result in two years imprisonment.

Raj, 26, an Indian citizen from Delhi, who asked to only be referred to by his first name, believes that Gandhi’s fall from grace cannot only be attributed to his conviction.

“Online, there has been such a propaganda against him that still continues to persist that even if people see a good thing that he does, the bias [against him] is so ingrained that you can’t help but treat him as a joke.”

Throughout his tenure in office, Modi has enjoyed consistently high approval ratings. Sivakumar comes from a suburban part of Tamil Nadu, and noticed how much electricity availability has improved in his hometown when he visited in summer 2023, among other improvements in living conditions.

“Back [in 2011] we’d have power maybe 20-30% of the time,” Sivakumar said. “When I go back now there’s electricity 80-90% of the time. There’s things that are a lot more modern. There’s new technology everywhere… Stuff like that resonates with voters, they can see how their quality of life has become materially better under the BJP.”

“Even if they may not agree with some of the Hindutva policies of the BJP, they can live with that [knowing] the benefit that Modi has provided compared to previous governments.” Sivakumar added.

Modi enjoys stronger support in the lesser-developed northern states such as Uttar Pradesh and Gujarat (Modi’s home state), where there is a higher concentration of Hindus, and has struggled to control wealthier and more developed southern states like Tamil Nadu and Kerala.

Modi is also accused of using tactics to solidify his personal standing and that of his party that resemble those of many authoritarian leaders. The BJP has pursued and intimidated various journalists and opposition political leaders.

On March 21, the Enforcement Directorate, a government agency tasked with investigating financial crimes, arrested Arvind Kejriwal, part of the opposition Aam Aadmi Party, on a corruption probe. The timing of this action by the authorities means he likely won’t be able to run in the upcoming elections.

Modi also made national headlines last year for invoking emergency laws to ban the screening of a BBC documentary probing his involvement as the Chief Minister of Gujarat in the notorious 2002 Gujarat Riots, where at least 1,044 people died, the majority being Muslims. The incident was one of the worst outbreaks of Hindu-Muslim violence in modern India, since partition.

Despite worries about the fairness of the context in which the upcoming elections in India will be held, Sivakumar believes that there’s no risk of actual electoral fraud.

“People make a mountain out of a molehill,” Sivakumar said. “There’s electoral committees, there’s proper oversight, there’s watchdogs, there’s every sort of concern that you would find in a modern democracy.”

Raj believes the fairness of an election extends past the polling station.

“Fair and free elections don’t happen right inside the booth, they happen [in] the period preceding it, and with respect to how India is right now, with respect to jailing opposition leaders… I don’t think it’s fair to say it’s going to be a fair and free election” Raj said.

With the likely reelection of Modi, Raj predicts more discrimination against minorities in the country.

“[With Modi’s reelection], you’ll see that there will be a large amount of laws targeting Muslims, laws targeting religious conversion, along with the militarisation of vigilante justice taking place, and weakening rule of law.”

With a third Modi term in sight, Sivakumar believes a strong opposition is needed to keep the BJP accountable in the future.

“Any party that has too much time in government ends up with not enough new policies,” said Sivakumar. “I don’t think that the BJP is at that point yet – but, at some point, there needs to be opposition that is strong enough to the BJP that they’re forced to innovate.”

By Oliver Dashwood