As Black History Month comes to a close, we remember the challenges Black people have faced, what they’ve overcome, and what they have contributed to society.

Washington, D.C., was at the forefront of emancipation, freeing enslaved people nine months before Abraham Lincoln in 1862. By 1900, D.C. had the largest percentage of African Americans of any city in the United States with more Black people coming because of opportunities for federal jobs and the quality educational institutions like Howard University.

Despite D.C.’s early emancipation proclamation, the lives of Black Washingtonians were still plagued by discrimination and racism. “[White people] called you all kinds of bad names back then,” Jarice Parrish said.

Parrish is Candie Simpson’s grandmother who is freshman, Morgan Simpson’s mother. The Simpson family has lived in the D.C. area for 86 years.

Parrish was born in Newberry, North Carolina, in 1935. Her mother passed away when she was born so she went to live with her grandmother in Alexandria, Virginia.

She remembers segregation. “We couldn’t go to stores where [white people] went, we couldn’t sit down at counters and eat, just because you were Black,” she said. “When you wanted some water you had to make sure you drank out of the spigot that said ‘Colored’ or ‘Negro’ or ‘Black’.”

Parrish attended Parker-Gray High School, an all-Black school, due to racial segregation. “We weren’t getting a good education like the other kids were getting so we had no way of getting a good job because we weren’t taught anything like they were,” she said.

She started working when she was nine years old, serving trays at a hospital. During her adult life, she worked in nursing. “I was into medicine. I loved it,” she said. She had always wanted to be a surgeon but didn’t have enough money.

Parrish also worked with children her whole life and had 15 children of her own. She raised them in D.C. when racial integration was starting. “I told them, ‘you can do anything you want to do’,” she said.

Parrish has faced many challenges in her life but said that the biggest one was the increasing cost of rent in D.C. “Every year your money doesn’t go up but your rent keeps going up,” she said. “I had to take homes I didn’t want to take because I had so many children.”

Candie and Morgan can’t imagine what Parrish went through. “There was so much more racism than there is today,” Morgan said. “They had to be so strategic about everything, just to stay alive, just to live,” Candie said.

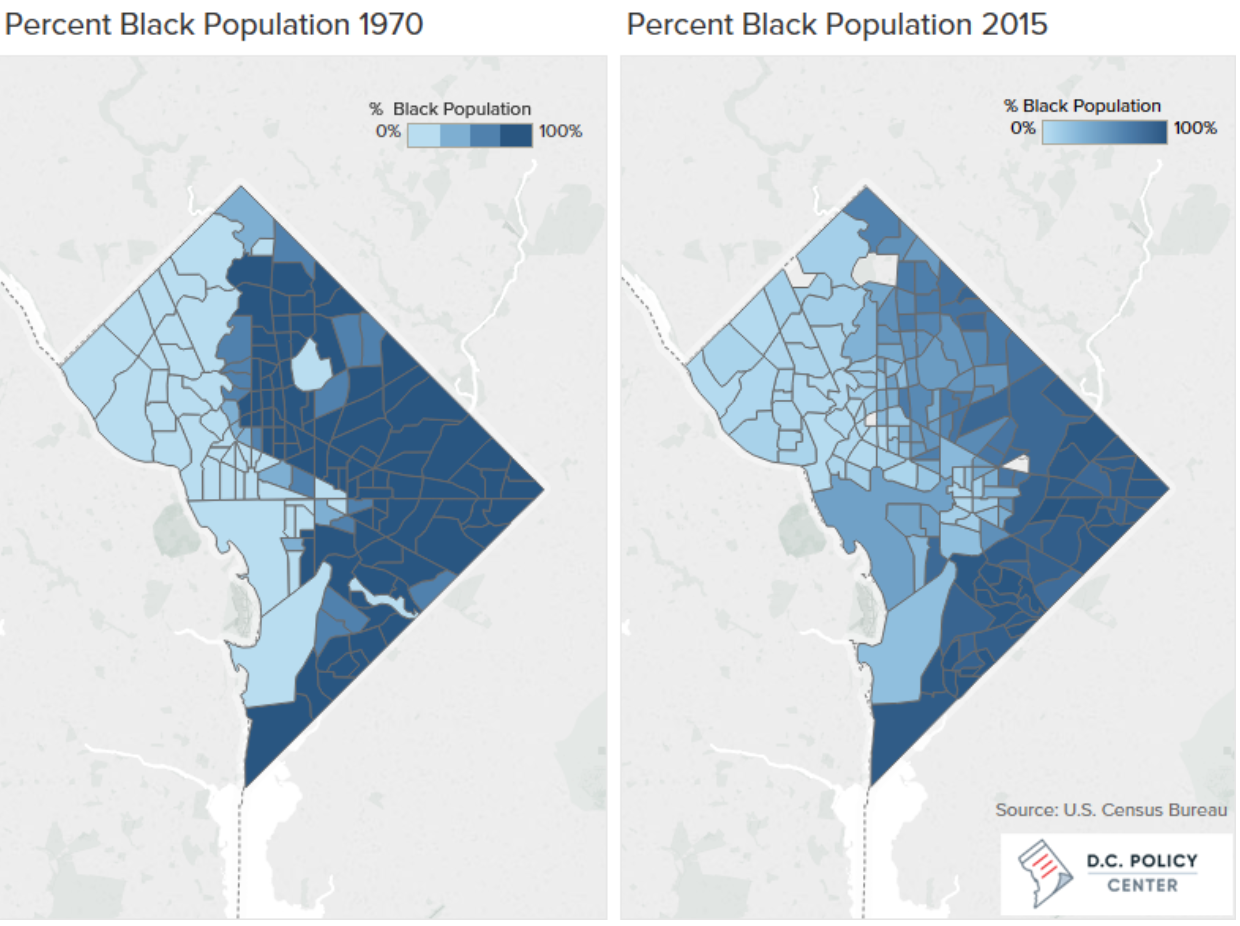

Candie was born in Washington, D.C., in 1981 when around 70% of the city’s population was Black. “They used to call it ‘Chocolate City’,” she said. “There was a large sense of community [and] it was a pretty cool place to grow up.”

There was a lot of violence in D.C. when Candie grew up but she was never involved in it. “It had always felt like a safe place,” she said. “The [cops] were our neighbors, our church friends, our school teachers.”

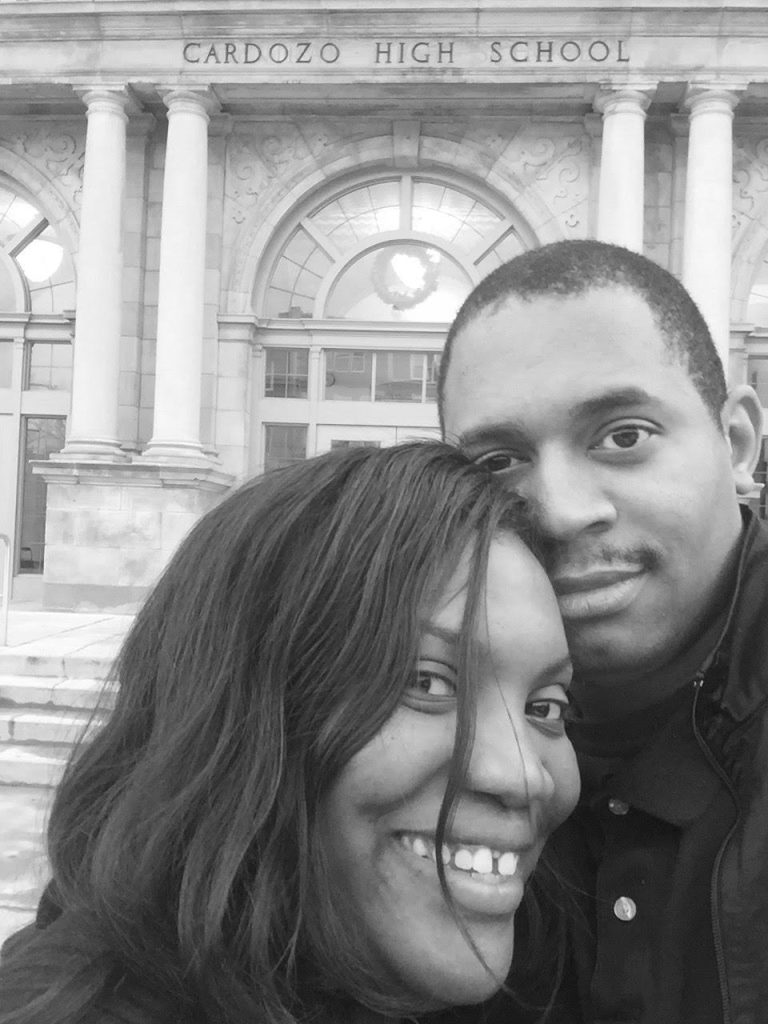

Candie attended Cardozo Education Campus, “We had access to many things, so many different learning experiences,” she said.

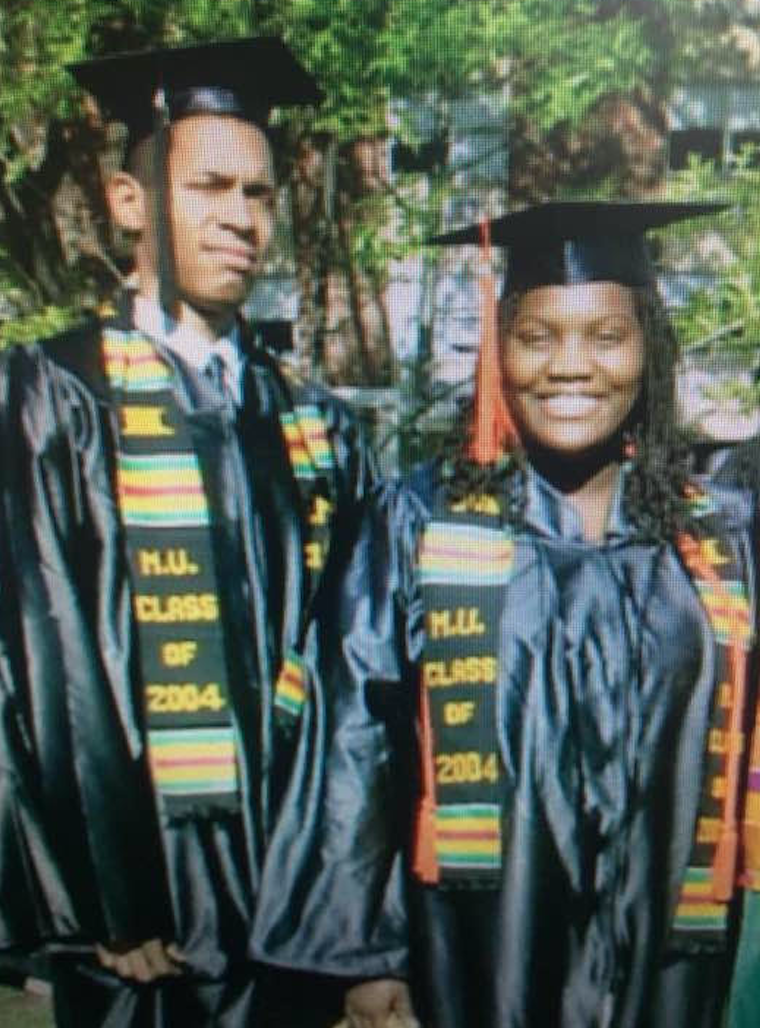

After high school, Candie went to Marshall University in West Virginia. She considers the university to be “the most racist place” she’d ever been. “One time I had somebody pull a gun on me and [my husband] at a Subway restaurant, for no reason at all,” she said. “They just didn’t want us in their sandwich shop.”

Candie stayed true to herself and persevered through the oppression. “I knew my roots, I knew what was right because I had come from here,” she said.

Even at school, many people had never seen a Black person. “People would ask me if they could touch me,” she said.

“Coming back home was on my number one list to do,” she said.

When Candie came back from college, the city had changed. “The cost of living was astronomical,” she said. Many people that she knows have had to leave D.C. because they couldn’t afford to stay. Sometimes, white people knocked on Black peoples’ doors and told them to leave so that they could move into their houses. “Just trying to keep my stake in the ground and keep myself anchored here has been really difficult,” she said.

Still today, low-income residents are being pushed out of neighborhoods at some of the highest rates in the country, according to the Institute on Metropolitan Opportunity, which tracked demographic and economic changes in neighborhoods in the 50 largest U.S. cities from 2000 to 2016.

A new study ranked D.C. 13th on the list of “most intensely gentrified” cities across the country from 2013 to 2017.

Candie has also faced wage discrimination. ‘There have been challenges with pay. I would know that people who were working in the same position as me or doing less work were getting paid more than I was,” she said.

She is a psychotherapist and she recently started her own practice. “That’s a part of why I’ve decided to work for myself,” she said. “I know that there are things that exist that I don’t have control over and if I’m going to be making people money and they don’t treat me well, I’m gonna make my own money and keep it.”

Though D.C. has very high rates of gentrification, it feels like a liberal town to Candie. “I’ve always felt like there are opportunities here and that if there was something that I wanted to do while I was here I could do it,” she said. Five generations of her family live in D.C. and she feels that it’s a good place to raise her children.

Morgan was born in D.C. in 2006 but lived in Maryland for about 8 years. “Everyone looked like me… so I didn’t feel like I needed to try hard or do anything to make myself feel confident or look good,” she said.

When she moved back to D.C., she explained that it was hard to fit in at times because she was mostly surrounded by white kids. “Being surrounded by a different crowd was hard to adjust to,” she said.

At first, Morgan only tried to make friends with Black or multiracial kids. Now she understands that race shouldn’t matter when making friends.

“Until I got to high school I had never really seen people from other cultures. It was probably one of the most important experiences for me as a young person to start learning about other cultures and other people. Learning about all the many ways that we are different but so many more ways that we are alike, and that led to a rich cultural experience,” Candie said. “And so for Morgan, that has been really important for me as a parent to make sure that she got exposed to those things early on so that it wouldn’t be a culture shock. It teaches her empathy which is incredibly important.”

Morgan started at WIS in sixth grade. “WIS is very accepting and inclusive… that has helped a lot because I’m not like ‘oh I stand out’ or ‘oh I’m different’,” she said.

(Students have varying opinions on how inclusive WIS is for students of color: Washington Post column on WIS sparks racial reflection)

Though she hasn’t experienced much racism, she has struggled with beauty standards. “Coming back to D.C. I felt like I had to straighten my hair, I had to have a smaller nose, I had to do all these different things to feel like I fit in or to be accepted by people,” she said. “I kind of feel like less than a person sometimes because I’m Black or I feel like I’m not good enough or I’m not smart enough or strong enough, not pretty enough solely because I am Black.”

Morgan feels that she has a special bond with other Black people. “The connections that I have with other African American people are definitely more special I guess because we can all relate to certain things,” she said.

One of the recent events that Morgan has bonded over is police brutality. “It’s so terrible that I don’t understand how you could just hurt these innocent people solely because of what skin color they are,” she said. “And then with the George Floyd thing… words can’t even describe how upset I was at that.”

Morgan does, however, think that the George Floyd incident was a good wake-up call. “I think the George Floyd situation brought [racism] to attention or like more than it has been in the past, and I think that has also allowed me to educate myself on different types of racism,” she said.

The past year has seen much progress in Black history with the election of Kamala Harris as Vice President. “When Obama was elected and Kamala just being elected this past year, I thought that that was amazing, and it inspires so many people,” Morgan said.

Parrish agrees. “We’ve come to the realization where if one person can do it, we could do it too,” she said.

Parish recognizes the progress made in her lifetime. “Everybody is getting on an equal base,” she said. “They definitely weren’t equal when we were coming up.”

Though progress has been made over the past 86 years, there is still a long way to go until Black people are treated equally in the United States. “It’s a huge task,” said Candie.

The three women share their wishes for their children and for future generations of Black people. Parish hopes that they have more opportunities. Candie wishes that they will be able to live their lives without being automatically judged because they’re Black. “I wish for them just to be free, to freely be themselves,” she said. Morgan hopes that her children will never think to themselves that they can’t do something because they are Black, “I wish that everyone could be accepting and welcoming and happy.”

To make their dreams a reality, Candie and Morgan Simpson recommend having conversations to develop a better understanding and compassion for one another. “The most important thing is just letting people know that we’re all human,” Morgan said.

By Zoe Hällström