Daniella Zalcman, award-winning visual journalist, gave a compelling closing ceremony keynote speech at the DC GIN Conference highlighting the power of photography in raising awareness about global issues.

Zalcman grew up near the DC area, studying at Holton Arms school in Bethesda, and later attending Columbia University, from which she graduated in 2009. A self-taught photographer, she became intrigued by human rights and reform, and began to take interest in ethnographic studies. Her main civil rights focus self proclaimedly tends to revolve around gender identity; “because I think that is the defining struggle of our generation.” She believes there to be so much controversy around the topic that it requires open communication and exposure.

The Global Issues Network Conference took place at George Washington University on March 14th-15th. At GIN, students from various DMV schools joined together to discuss important, current international crisis and events that will most likely be part of our struggle to solve as we move into adulthood as a large student body. Zalcman delivered the closing keynote speech on Tuesday afternoon.

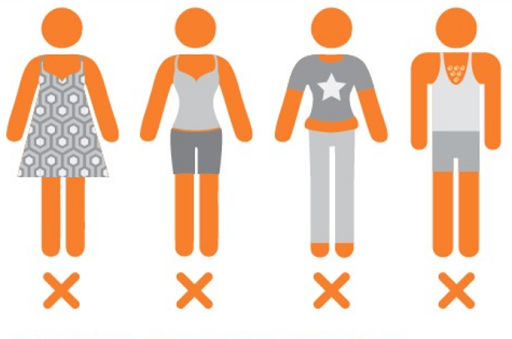

The first of her projects she spoke of was regarding the criminalization of homosexuality in some West African countries such as Uganda. This series required her immersion into a community that lived in fear of being discovered by law enforcement officials. It consisted of an abstract portrayal of the piercingly repressed Ugandan LGBT community. Zalcman spoke of the gay rights activists in Uganda with utmost respect, as they compromised their safety for the right to be themselves. This dynamic complexified as Zalcman found herself in situations in which she knew that if she published or released her work, she endangered those she profiled. She emphasized that “the hardest part of [her] job is gaining the trust of [her] subjects, especially when their lives and well-being are at stake.”

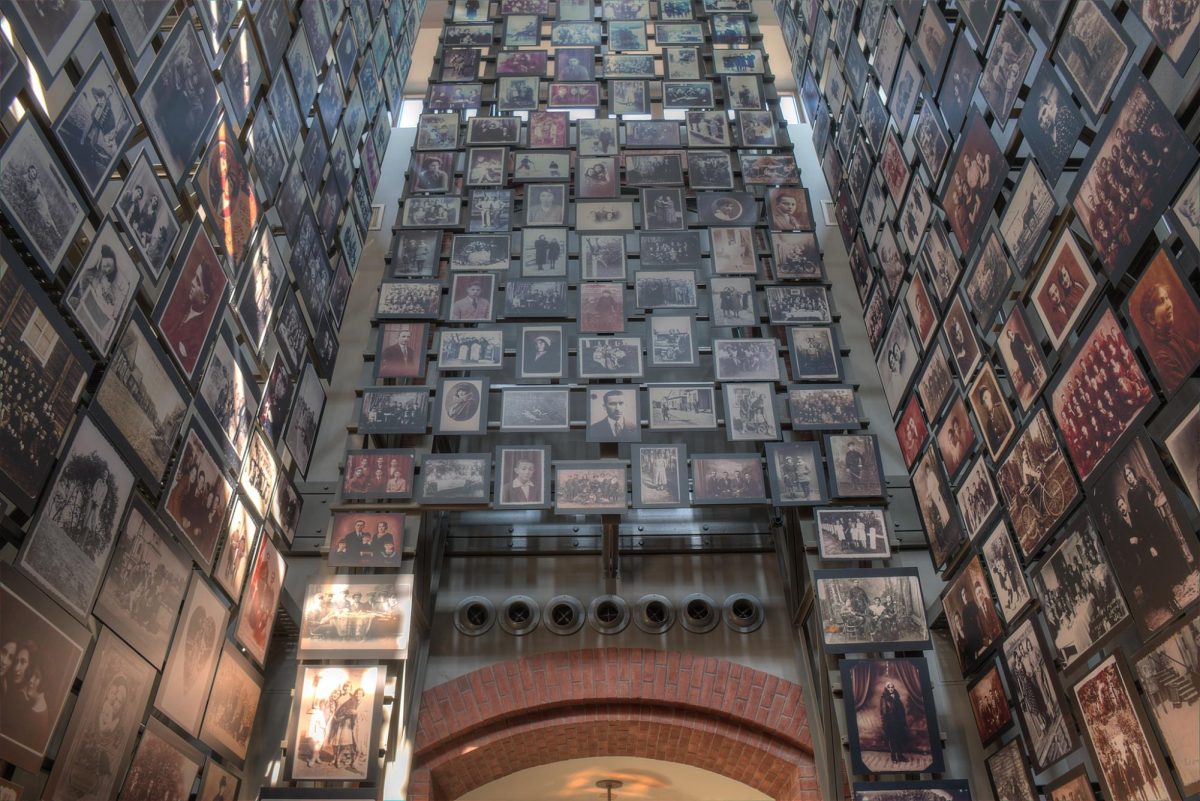

In a newer project, Zalcman investigated the traumatizing history of Canada’s indigenous populations. A subject which the majority of the student’s had never heard about until that Tuesday, this population endured a horrifying level of abuse and discrimination. The result of the torment was essentially the obliteration of the entirety of the indigenous culture, its practices and language. Zalcmans’ portraits of members of this lost society combined with stories of individuals and quotes created a silence across the auditorium that fundamentally captured the power of her form of activism. Her unconventional use of the multiple exposure photograph seemed almost overly artistic for a news story, yet it highlighted the aspect that made the entire report so shocking; that it was previously unseen.

The question often surrounds ethnographic photojournalists regarding the extent at which they can maintain objectivity. Zalcman believes it’s silly to expect from a reporter in such a controversial environment to be completely empirical, but that it is crucial to represent both sides of a story. She, undoubtedly, has a strong opinion on the matter, to be raising awareness on the topic in the first place. But she considers it her basic duty to report accurately and not leave out any important component of a conflict. This attitude can become incredibly effective in realistically achieving change.

After her speech, when she opened the floor for questions, WIS sophomore Jessica Jackson asked perhaps the quintessential question, “Why am I just hearing about this? Why isn’t this something we know and read about?”

Although so many of the world’s hardships remain hidden and unaddressed, Jackson’s question set the perfect tone for the discussion of where to go from here, and what students could do to get involved.

Zalcman believes that although photos are an interesting and effective method of communicating and informing people in some ways; they are quite limiting in others. “Photography is just something that came quite naturally to me,” reporter says. A photo can literally put a face to a story, an act which in and of itself makes it more conducive to empathy. But any form of research and exposure is essential in the journey of achieving a better future, because it gives us a place to start.

“You erase people’s history when you don’t talk about it,” Zalcman claimed.

By Val Deshler