The student section at the WIS soccer field was decked out in black, accompanied by a loud and persistent drum beat as the clock on the scoreboard ticked down. Students shouted the familiar “I believe that we will win” chant, with their faces streaked with red paint and high hopes. The day was Nov. 11, 2022, when the WIS Boys Varsity Soccer team was playing one of their rival schools, Jackson-Reed High School, in a tense DCSAA semi-final game.

Soccer has the most participants of any sport at WIS, with 111 total members in the Upper and Middle School teams, and historic games like the previously described game against Jackson-Reed have particularly more spectator turnout than any other sports competitions at WIS. Yet most schools in D.C., along with over 15,000 other U.S. high schools, also offer soccer’s red-white-and-blue alternative: American football.

There are nearly two and a half times more high school boys participating in American football than in soccer in the U.S., but WIS doesn’t offer the traditional American sport.

The WIS athletics program is part of the Potomac Valley Athletic Conference (PVAC), and the sports that the school participates in are structured by its rules, according to WIS Director of Athletics Floreal Pedrazo.

“To be part of [the PVAC], you as a school are required to have competitive teams in [its] sports,” Pedrazo said. “Right now, we fulfill those requirements.”

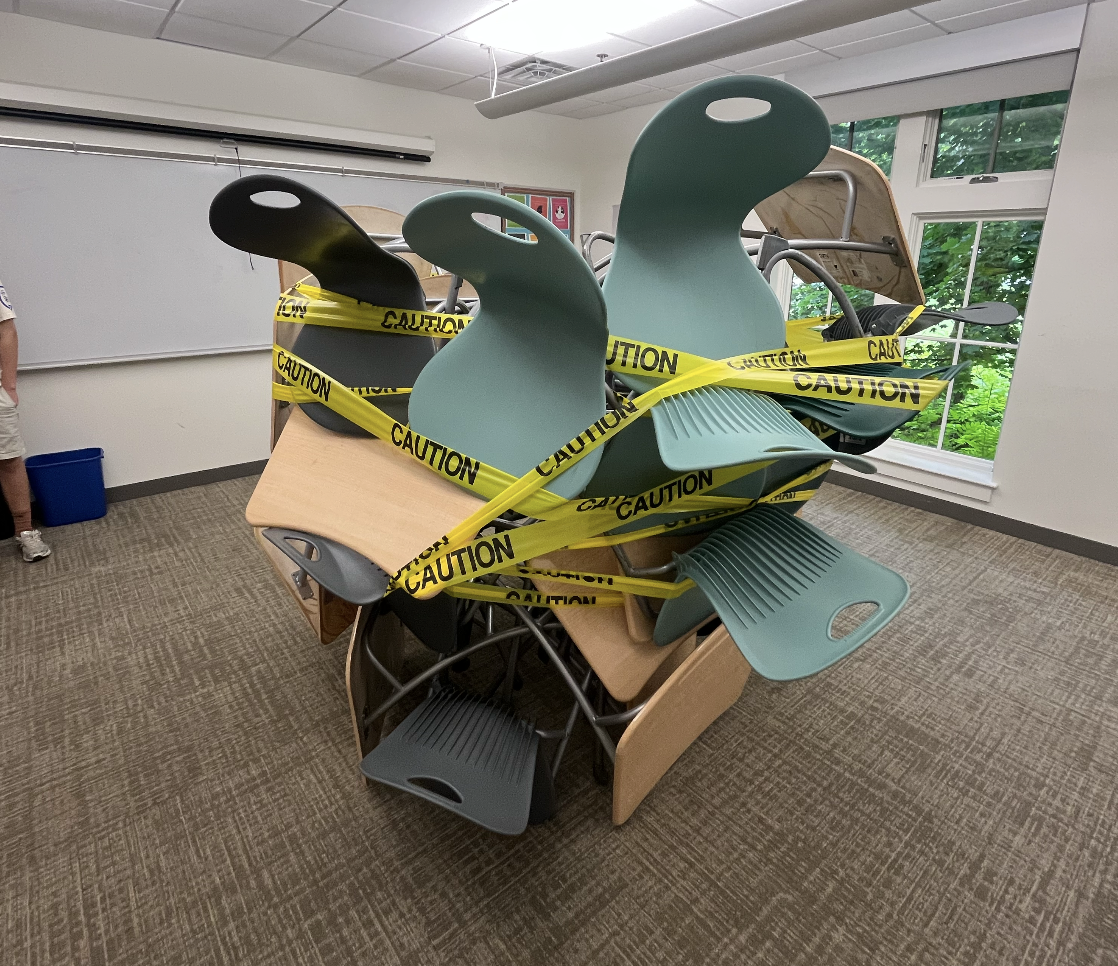

American football is not one of the sports in the PVAC, which Pedrazo believes is a result of the sport’s cost, size, and impact.

“Football completely changes a school’s athletics program,” Pedrazo said. “You need bigger lockers, more people. You need to bring in more donors because football is an expensive sport.”

In order to add a sport like football, the WIS athletics budget would need a sizable upgrade. Most schools spend tens of thousands, if not millions (in the most extreme cases), on their football teams.

Junior Rupert Wallace, who has played American football outside of WIS for two years, also cited possible financial reasons for the sport’s absence at WIS.

“It’s not a cheap sport to have,” Wallace said. “You have to get all the equipment. It’s definitely more expensive than soccer or basketball.”

Beyond financial deterrents, the addition of American football as a sport at WIS would mean competing outside the PVAC, which is entirely possible, but very risky, according to Pedrazo.

“If we’re struggling to fill the teams that we should, there’s a risk that adding a new sport would cannibalize the sports we already have,” Pedrazo said.

For every football team, 30 to 50 male players are required, a size far greater than any other team at WIS. That commitment is one that the school would have a hard time reaching. If anything, WIS has been struggling to fill its current sports teams. Two years ago, the school didn’t have a Girls Varsity Basketball team, which the athletics department had to work to fix.

“We implemented basketball at primary school, [and] we tried to increase the hype in middle school,” Pedrazo said. “Now we have a varsity team.”

WIS’ situation is uncommon in that its teams are all formed this way: internally and without external sourcing or recruiting. Many other schools in the area recruit students for the sole purpose of competing in their athletics programs.

“Admissions offices from other schools, like Sidwell, have admissions programs that meet weekly with the athletic director because they bring students in to play sports,” Pedrazo said. “We don’t bring students in to play sports; we recruit students within the student body to play sports.”

The focus of WIS admissions is on the school’s academics, as the rigorous curriculum is currently what attracts most new families. Athletics is often more of an afterthought to prospective WIS families.

“Right now, families come here because they see that academics-wise, it’s a top-notch school, and it’s an IB school,” Pedrazo said. “And then they see that there are athletics.”

WIS offers the IB because of its focus on international-mindedness, a quality that some believe would clash with the traditional American atmosphere of football. Wallace hypothesized that the school’s international focus is one of the reasons why implementing American football might be difficult.

“Football is a really American sport, and as an international school, the impact it would have would make it a lot more like other schools around here,” Wallace said.

However, WIS has found athletic success even though it doesn’t emphasize sports, with several WIS students playing college sports every year, though Pedrazo doesn’t take credit in any way for those victories.

“Often there are students that go and play college sports in sports that we don’t even offer,” Pedrazo said.

WIS alum Jake Drimmer now plays baseball at Oberlin College, for example, though WIS doesn’t offer a baseball program. Yet in spite of some students’ pursuit of college sports, Pedrazo noted that the focus for recruited students is often still on their education.

“Even when they are recruited, [WIS students] go to Ivy Leagues and top class schools to play [sports],” Pedrazo said. “Academics first, and then sports.”

But that is not to say that WIS performs badly. In fact, despite technically being an underdog due to a lower budget and no recruitment, the school does extremely well in the PVAC and often finds its competitive equal in schools with much higher budgets.

“Parents come up to me asking why we’re performing so well against other schools [that are recruiting athletes],” Pedrazo said. “And the answer is I don’t know. At WIS we have a lot of natural talent.”

Though WIS will likely never see American football on its field, its students will keep cheering loudly for its soccer teams as the clock on the scoreboard ticks down.

By Tindra Jemsby