This is the product of my 2019 10th Grade Project.

Ms. Liberty Rashad was at a family reunion in Winthrop, Maine when Hurricane Katrina struck in August 2005. From the news, she found out about the massive waves that came “crashing down on neighborhoods and just destroyed them, turned them upside down,” waves that killed nearly two thousand people and flooded her city of New Orleans.

Worries consumed her. She worried about her children and grandchildren, who had lived in New Orleans. She worried about her friends in the city, many of whom stayed and waited out the storm. She worried about her house, too. Much of her livelihood depended on that house: she rented out three of its four units. Any damage to her home would take years to repair. If her house flooded, her tenants would have to leave.

Her house had flooded. Katrina drowned her basement and ravaged her roof, leaving a hole. But she was very lucky. At least she had electricity. Two weeks before Katrina, she’d been hired at a job outside of New Orleans; she didn’t completely lose her livelihood. Her house was broken and battered, but it still stood strong. And she had insurance.

“I was highly, highly lucky,” she says. “I feel very fortunate.”

***

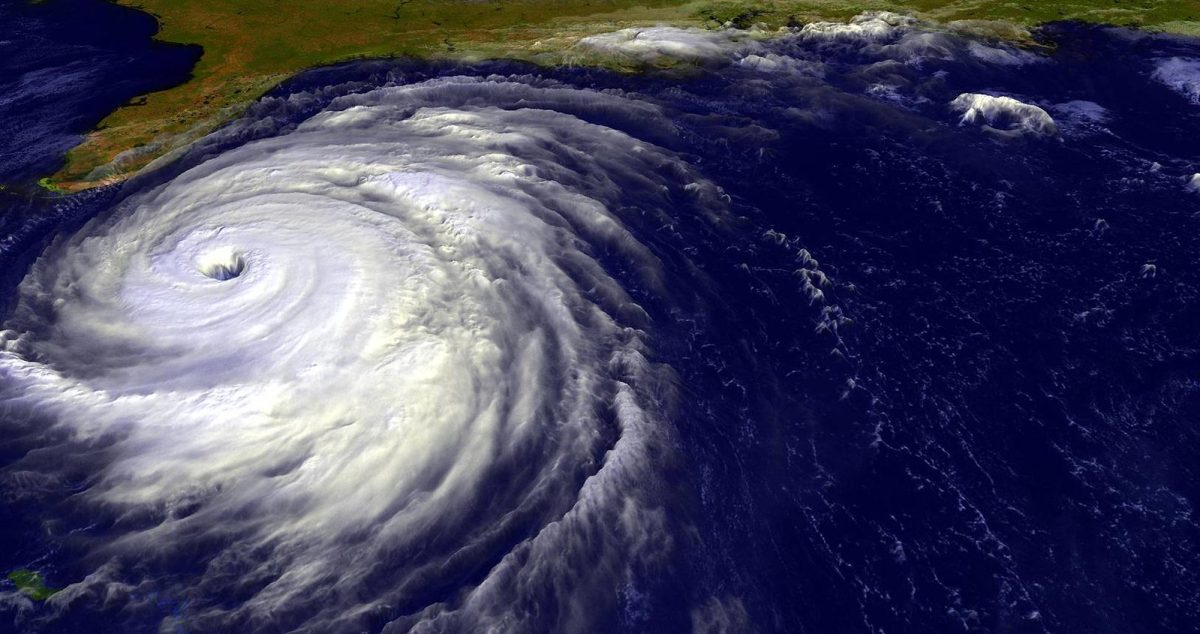

On August twenty-fourth, 2005, Atlantic waters around the Bahamas baked in eighty-five-degree heat. Hot, humid air began rising and condensing into storm clouds. The condensation process released heat, warming the air beneath the clouds. This new air also rose, condensed, and heated the air beneath. The cycle of air rising, condensing, and releasing more heat created hot winds that circulated around a newly-formed center. Katrina was born with eighty-mile-per-hour gales, a Category 1 hurricane. It brushed past southern Florida, killing eleven people and causing power outages as it headed toward the Gulf of Mexico.

Most dangerous tropical storms and hurricanes stay at sea and fade away before they can make landfall. But as Hurricane Katrina churned toward the southeastern United States, temperatures in the Gulf of Mexico reached nearly eighty-seven degrees. Feeding off this heat for three days, Katrina grew from a Category 1 into a Category 5 hurricane (the highest possible rating) with winds reaching up to a hundred and sixty miles per hour.1 On the twenty-sixth of August, Louisiana and Mississippi declared a state of emergency. Traffic was jammed along highways and in cities as people tried to evacuate. In New Orleans, shelters were set up for everyone who couldn’t evacuate, but few other preparations were made.2 The hurricane was fast approaching land, now as a Category 4.

Katrina slammed into the Gulf Coast on August twenty-ninth with winds clocking in at one hundred and forty miles per hour. Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama bore the brunt of the storm. The hurricane wreaked havoc on the Gulf Coast for twelve hours, killing one thousand eight hundred and thirty-three people before finally slowing to a tropical storm. By August thirtieth, it had ceased completely.

New Orleans, a city partly below sea level and sinking, took the heaviest blow. Katrina’s effects there were devastating. While winds and waters were to blame for tearing up the city, it was the failure of levees and floodwalls neglected by the Corps of Engineers that caused most of the flooding. Eighty percent of the city was underwater. Seventy percent of housing units were damaged or destroyed. Floodwaters wrecked power and water sources, dragging in sewage and bacteria. What few medical centers were left were too disorganized to cope with the outbreaks of disease such as West Nile and endotoxin-related diseases. Mental illnesses such as PTSD gripped twice as many New Orleans residents as before the disaster.

Over one hundred and ten thousand households remained in FEMA-subsidized trailers a year after the storm, still unable to find a new home. The caregivers of each of these families were often disabled “due to depression, anxiety, and other psychiatric problems.” A common cause of these mental illnesses and psychiatric problems was an absence of social support to rebuild victims’ lives.

The people who were hardest hit were the city’s poor, eighty-four percent of whom were black.

***

When Ms. Rashad returned permanently to New Orleans in December 2005, she found a city in ruins. Cleanup efforts consisted of local and state responders distributing mops and cleaning products. There was still some flooding four months after the hurricane.

Even today, Ms. Rashad remembers how New Orleans’s infrastructure crumbled in Katrina’s wake. Fire departments couldn’t reach fires on time. Mismanaged businesses were trying to give out loans. Communication with the outside world was nightmarish. The only way to get mail was to wait and wait once a week at a “postal distribution location.” Other than that, “the only thing you really had was a telephone,” she said.

Social institutions that people relied on had disintegrated — a case in point was the school system. Louisiana state government used Katrina’s chaos as an opportunity to turn public schools into private and charter schools. Many teachers lost their jobs. Some teachers who had evacuated the city had to take an exam to come back, since their former schools were now charter or private. Some parents sent their children back to New Orleans unaccompanied, expecting the schools to be open. When they arrived, these children had nowhere to go and were left homeless and alone. The chaos of New Orleans’s public schools mostly affected black students since they made up the vast majority of those enrolled in public school.

Unlike many people, Ms. Rashad did have home insurance, but finding a good contractor proved impossible; contractors weren’t taking clients because they had to help themselves, their families, and their friends. The police department was “brutalizing and killing” people as theft skyrocketed. Entire rescue operations were halted to arrest people committing crimes. Wild dogs—former pets—roamed the streets. Garbage, along with people’s ruined belongings, were put on the side of the road, but there were no city services to pick them up. They just sat there. Ms. Rashad said, “It was sort of like the apocalypse.”

***

Victims with the lowest income were the worst affected by Katrina. In September 2005, President George Bush gave a speech addressing the disaster in which he recognized that poverty in affected regions such as New Orleans “has roots in a history of racial discrimination” that made the city’s poor communities—the ones most hurt by Katrina—overwhelmingly black. It was a history stretching back centuries. In the early eighteenth century, French colonial Louisiana lived under a system of laws called the Code Noir. Its laws made Catholicism the only recognized religion, prohibited interracial marriages, suppressed interactions between black people and white people, restricted the rights of both enslaved and free black people, provided rules and conditions for the freeing of slaves, required masters to recieve approval from the city’s Superior Council in order to free slaves, and gave guidelines for appropriate punishments if the Code was broken. For white people, these penalties usually took the form of fines. Colonial officials and masters punished disobedient slaves with whips, branding irons, and knives.

Spain took New Orleans in 1763 after signing the Treaty of Paris. The city spent nearly forty years as a Spanish trading partner with Cuba, Haiti, and Mexico. Under Spanish colonial rule, a prominent class of free black people emerged as Spanish racial views were more liberal than French ones. In 1800, Spain gave Louisiana back to France. Three years later, it was sold to the young United States as part of the Louisiana Purchase.

New Orleans quickly became home to the American Deep South’s biggest slave market. Between 1804 and 1862, over one hundred thousand people were sold there, ripping apart families and subjecting untold men, women, and children to endless, torturous labor. In the 1850s, sugar plantations in Louisiana along the Mississippi River produced around four hundred and fifty million pounds of sugar each year, making millionaires out of white plantation owners whose profit relied on the possession of captive human beings.

New Orleans surrendered itself to Union troops in 1862, the second year of the American Civil War. Since the city’s economy was built on the backs of slaves, an end to slavery meant an end to soaring profits and an economic collapse. Newfound racial tension emerged as resentment between freed slaves and former slaveholders brewed. This tension became increasingly class-based as poor immigrant workers from Europe sided with freed slaves. The New Orleans Riot in 1866 set the stage for race riots erupting through the American South during Reconstruction. Racial divides became political battlegrounds as conservative newspapers published rumors of government instability to win sympathy for the Democratic Party.

Racial tensions in New Orleans didn’t die with the Civil War. A century later, in November of 1960, public school desegregation sent Ruby Bridges to William Frantz Elementary in New Orleans. She was the first black student to be enrolled at William Frantz and was a symbol of the city’s racial integration. Violent mobs of white segregationists threatened and harrassed the six-year-old on her way to school every day. Every other student in her class had been pulled out by their furious parents. In retaliation for her refusal to leave school, her grandparents were evicted from their farm.

Such racial tensions and disparities continued long past the advent of the Civil Rights Movement in the sixties. Racial discrimination was alive and thriving in New Orleans through the birth of the twenty-first century. And in 2005, after the most destructive storm the city had ever witnessed, this long history would be put to a new test.

***

Did Ms. Rashad notice any such discrimination in New Orleans before Katrina? “Oh, absolutely…. It was the way things were,” she says. The city had never recovered from its brutal history of racial economic disparity. From the moment Ms. Rashad moved to New Orleans in 2000, it was right in her face. “It was glaring…. Who had the jobs, who made the money, who had the good housing stock.” Certain streets were known for having “big-money jobs,” she explains. They were the jobs with power and money, the big corporations. Even though most of the city’s population were black, everyone she saw streaming from those buildings were white people who usually came in from the suburbs outside of the city. New Orleans streets were lined with “white blocks” and “black blocks…. You had poor black people living on one block and then [white people in] huge mansions on the next block.” “The checkerboard,” it was called.

The schools were segregated, too. Although school segregation hadn’t been written in law for decades, public and private schools were heavily segregated based on race and income. White flight was rampant. Many white families had left the city during public school desegregation in the fifties and sixties.

“There weren’t any white children in the public schools at all,” says Ms. Rashad. “Period.”

While white children went to private and charter schools with a few black children, the vast majority of black children went to public schools. White parents didn’t want their children going to public school with poor black children, Ms. Rashad says. The public education itself system was not “up to par.” Only local government wasn’t white-dominated because the population voted representatives into office. But real power, Ms. Rashad says, was still in the hands of slaveholders’ descendants. These white families were the ones with the “big-money jobs” and the ones sending their children to private school.

Even the good jobs in the government were subject to favoritism because black representatives imitated what white representatives “had been doing for all those years,” giving the jobs to their close connections. To make matters worse for the poorer residents of New Orleans, the state government took money from the city’s tourist industry to fund the rest of the state, and very little returned to the city. The public school system was failing. The criminal justice system, Ms. Rashad says, was “criminally unjust.” Black people were convicted of small crimes and sentenced harshly. At the time of Katrina, Louisiana had the highest incarceration rate in the United States.

***

Katrina’s aftermath showed the government’s willingness to neglect the city’s poor, primarily black population. But the disaster also drew attention to the centuries-old history of unequal opportunity between races that created those communities’ particular vulnerability in the first place. It pointed towards institutional racism: a racial hierarchy within a society, manifested in disparities in power, resources, and opportunity among different races.

When the hurricane hit, Louisiana had the second-highest poverty rate in the country. Poverty rates were especially high among New Orleans’s black community: almost sixty-eight percent of the city’s entire population were black, and eighty-four percent of the city’s poor residents were black. Poor households were even more likely to suffer Katrina’s full fury because they usually lived in cheaper areas and in housing more “susceptible to flooding” than wealthier residents. Those areas, such as the Lower Ninth Ward and New Orleans East, were below sea level and were, before Katrina, kept dry by the neglected levees.

The state government’s only evacuation plan was to warn people to leave the city. No other means of escape were provided. The swarms of lucky people able to evacuate created traffic jams, stalling and blocking their access to safety. Those who didn’t have a car couldn’t leave in time. Half of poor households and three in five poor black households in New Orleans did not own a car. They were trapped within their neighborhoods and had no choice but to wait for Katrina to pass. They could only hope the city’s levees would shield them from the floodwaters.

The inept levees crashed, unable to contain the fierce Atlantic waves. The neglected floodwall system failed and the city flooded. But the true failure lay in FEMA’s disastrous response to the wreckage caused.

FEMA donated nearly four billion dollars in housing assistance it provided for victims in Louisiana. FEMA, however, failed to provide aid for thousands more people who were in desperate need. In fact, a report by the Government Accountability Office concluded in 2006 that FEMA made at least one billion dollars’ worth in improper or fraudulent disaster relief payments. FEMA’s planning for the hurricane was catastrophic. In order to be approved, federal assistance had to be requested in a letter that worked its way slowly through FEMA before reaching the federal government. By the time real federal response arrived days later, the damage was done. The shattered Lower Ninth Ward had to wait ten months for the first trailers to arrive. It was the last area of the city to regain electricity and drinking water. Before Katrina hit, it was one of the city’s poorest areas, and its population was over ninety-eight percent black.

***

Environmental crises unmask the deep-seated disparities between wealthy and poor, those with access to resources and those without. Although Katrina was no exception, institutional racism is in no way unique to New Orleans or to the South. Nine years after Katrina, Michigan’s government directed the city of Flint to switch their source of drinking water to the Flint River while a new pipeline was being built to Lake Huron. The switch was intended to cut the cost of providing water to the city due to its economic decline after General Motors closed many of its Flint plants in the late twentieth century. Within days, residents found their water had changed color, smell, and taste. Researchers reported it contained dangerous amounts of lead.

Because Flint River water wasn’t treated with anti-corrosives, it was eroding through the iron water mains and lead service lines before reaching Flint homes.

Over the next eighteen months, at least twelve people died, killed by Flint’s contaminated water and by the local government’s denial of any problem with the water. State officials repeated over and over “that there was nothing to worry about. The water was fine.”23 Then-Mayor Walling said the water was “a quality, safe product” and that people were “wasting their precious money buying bottled water.” The city is still recovering today, with huge numbers of poisoned young children experiencing learning disabilities and slower development.

Was the Flint water crisis, like Katrina, related to institutional racism? At least one person believes racism was at its heart. Mayor Karen Weaver, who was elected the year after the crisis began, said that if Flint hadn’t been fifty-eight percent black, if it hadn’t had high unemployment and poverty rates, either the crisis wouldn’t have happened or officials’ response wouldn’t have been slow and “allegedly dishonest.”

“I was not the only person who thought this,” she said.

***

Was institutional racism at play once again with Hurricane Maria in 2017?

From August to September 2017, hurricanes Harvey, Irma, and Maria rattled the southeast U.S. Harvey and Irma hit Texas and Florida respectively. Maria struck Puerto Rico, destroying a third of its homes and killing nearly three thousand people.

Ninety-nine percent of Puerto Rico’s residents are Hispanic or Latino, while Texas’s and Florida’s Hispanic or Latino populations make up less than forty percent of both states. The United States has a terrifying two-hundred-year anti-Latino history involving illegal deportation, lynchings, systematic segregation, slurs, and forced repatriation.

The federal aid provided after each hurricane was less than equal. Puerto Rico needed tarps for temporary homes since so many were obliterated. Nine days after Maria, five thousand tarps were sent. That’s one-fourth of what was delivered after Harvey (twenty thousand) and almost one-twentieth of what was delivered after Irma (ninety-eight thousand). Hurricane Maria destroyed at least five times more homes than Irma did. It destroyed half as many homes as Harvey did, yet received one-fourth of Harvey’s housing support.

Along with the tarps came food aid. Under two million meals were delivered to Maria’s affected areas, in contrast to five million delivered after Harvey and nearly eleven million delivered after Irma. Food-stamp aid was provided at first, but Congress didn’t reauthorize it by the deadline in March 2018 because the Trump administration decided extra food-stamp aid was unnecessary. And yet, forty-three percent of the island’s residents depended on that aid for “groceries and other essentials.”

Only ten thousand federal personnel were deployed to aid in Maria relief efforts. Twice as many personnel were deployed after Irma and three times as many were deployed after Harvey. Half of those personnel addressing Maria were trainees or unqualified.

As of 2018, only half of those in Puerto Rico who had applied for FEMA housing assistance had received it because FEMA only grants housing assistance to people with certain property records. Many Puerto Ricans live in houses bought generations ago and no longer have legal proof of ownership. Some houses never had construction permits. For years, politicians have ignored any lack of proof or permit because informal housing meant less demand for affordable housing. But after Maria, FEMA denied those vulnerable citizens essential help in recovering from disaster.

President Trump refused to acknowledge any discrimination. In a tweet, he claimed the “great job” his administration did in the “inaccessible island” of Puerto Rico was “unappreciated” and overcame roadblocks such as “very poor electricity” and “a totally incompetent Mayor of San Juan.” He also said Puerto Rico’s relief effort was “the best job” he did, “an incredible, unsung success,” but that “nobody would understand that. I mean, it’s harder to understand.”32

Mayor Carmen Yulín Cruz of San Juan disagreed, saying the Trump administration “killed the Puerto Ricans with neglect.” She believes Puerto Rico does not have the supplies or the preparations to recover from another storm if it were to strike. “Shame on President Trump,” she said. “[The federal response to Maria] will be a stain on his presidency for as long as he lives.”

***

Katrina, Flint, and Maria were all twenty-first-century disasters. Each one was worsened by an American government’s neglect for a minority race or ethnicity. And each one revealed an institutional basis behind that discriminatory neglect.

Institutional racism is very hard to combat because the root of the problem lies in cruel injustices from centuries ago. To destroy American institutional racism would be to undo more mistakes than anyone can remember. Slavery, oppression and tension among races have existed in the United States since the first conflicts between European settlers and American Indians; they were built into our society the minute the first seventeenth-century slave ships touched American soil.

Disasters like Katrina magnify institutional racism in America with the utmost clarity, since discrimination towards certain racial groups is often a life-or-death matter. In every place in the country, certain communities have been marginalized for centuries. Those groups are shattered to the core during environmental crises because our brutal history denies them economic opportunities and backup plans. Then, our government denies them resources needed to recover.

Situations in all three crisis-affected areas remain bleak. Segregation in New Orleans is still evidenced in its now-charter school system, where almost all former public schools have upwards of eighty percent black enrollment. Flint, Michigan’s residents are still suffering from lead poisoning. Many Puerto Rican homes damaged by Hurricane Maria remain in disrepair. Tens of thousands of residents who fled the island are still displaced even today. Some are extremely poor and struggle to find jobs or decent housing outside of Puerto Rico.

What is the future of institutional racism and its role in environmental disaster response? Only time will tell. As the number of climate disasters rapidly increases with climate change, so will the number of government responses to evaluate. It appears undue burden from such disasters will fall on the minority groups who are already victims of institutional racism.

As for Liberty Rashad, she fears that institutional racism in her hometown of New Orleans is as pervasive as it was before Katrina. “Not too much has changed,” she says. “It’s still the same.”

Bibliography: https://docs.google.com/document/d/1Zj6TMbLMl86LIPLH1HJK42hJ75KqZ0XmoclI65sblQ0/edit?usp=sharing