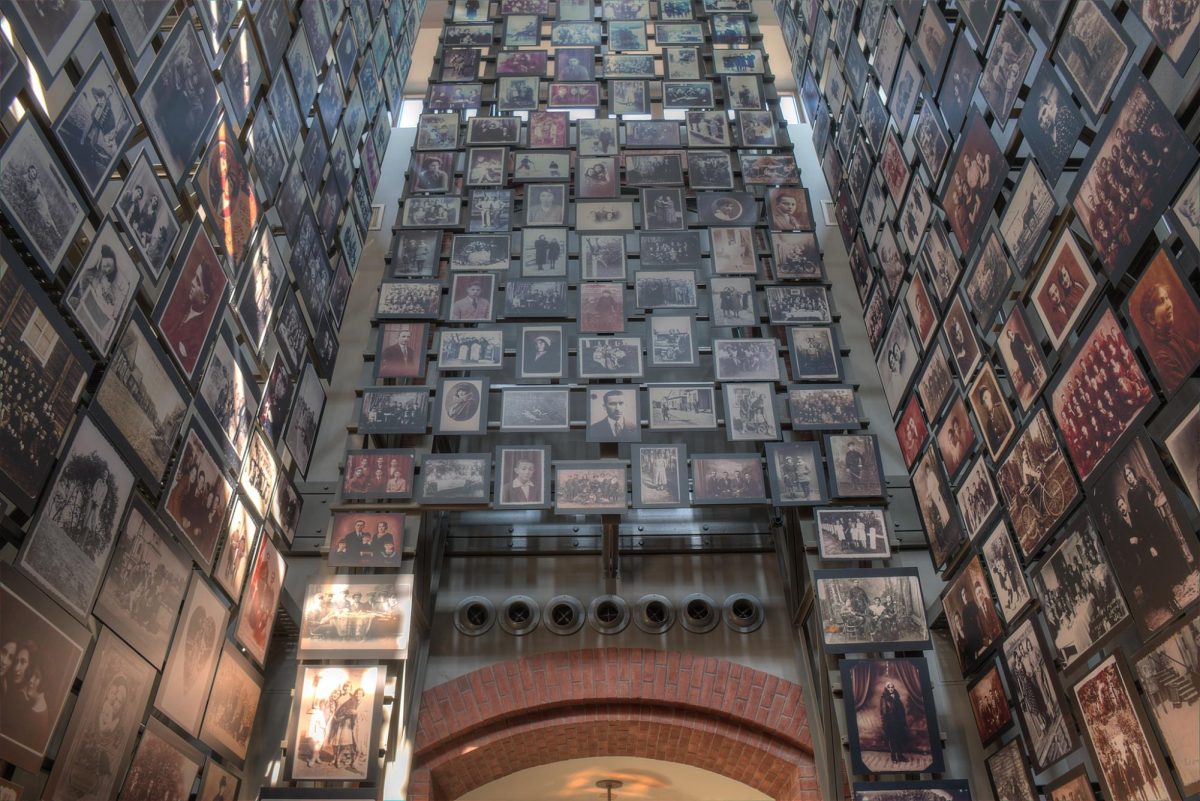

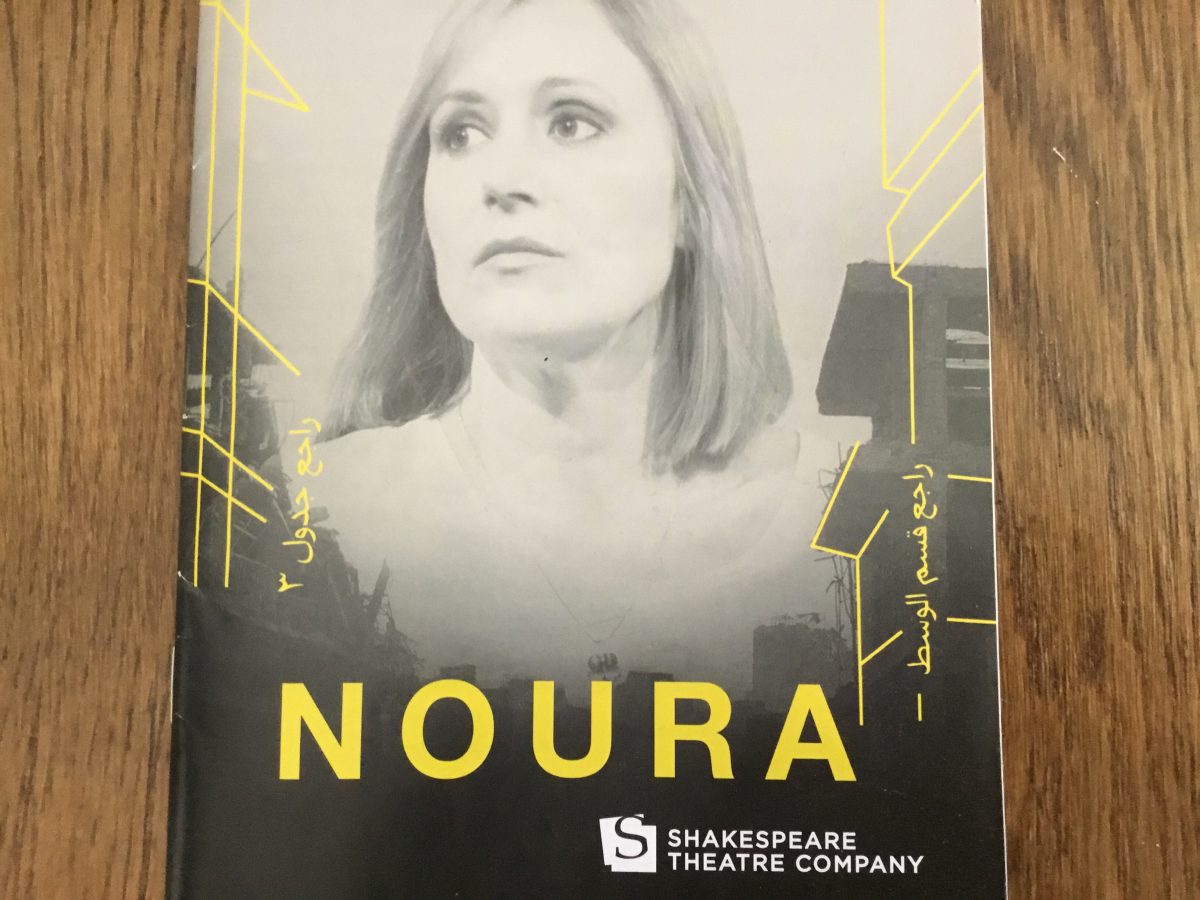

Bold and energetic, yet at times heartbreakingly raw, Heather Raffo’s Noura, a modern remake of A Doll’s House by Henrik Ibsen, explores the extremely relevant issues of immigration, identity, family, and sexuality across Middle-Eastern and American cultures today.

As the play was just beginning, maybe because of the warm colored, lived-in looking set, and the fact that it takes place two days before Christmas, I assumed that Noura would be a sweet, fun-loving show during which a family experiences some brief conflict, ultimately ending up resolving the issue and eating Christmas dinner next to a well-lit tree as if nothing had ever happened. That couldn’t be further from the truth. Noura centers around a middle-aged Iraqi woman, Noura (Heather Raffo), who fled from the city of Mosul when she was a young woman, and now lives in America with her husband, Tariq (Nabil Elouahabi), and her son, who goes by both Alex and Yazen (Gabriel Brumberg). Noura’s decision to invite a twenty-year-old Iraqi refugee, Maryam (Dahlia Azama), to their Christmas dinner thickens the plot, as nobody expects the young university student to be six months pregnant. Noura and Tariq’s varying opinions of Maryam’s situation cause some of their deeply buried doubts, insecurities, and secrets to resurface.

Additionally, something I love about Noura is how Raffo’s characters are written explicitly to go against stereotypes of certain people or cultures that Americans are often faced with. Maryam, for example, is not a pity-inducing Iraqi refugee who comes to America broken and traumatized. She is a confident young woman who is not afraid to speak her mind; it is clear that the tragedies she experienced in Iraq did not weaken her, but rather served to make her strong and determined. Azama plays this role extremely well: her loud, clear speech and smooth gait make her every word and action feel carefully calculated, and exude a sense of purpose. Noura and Tariq’s relationship is also very unlike what I imagine a traditional Middle-Eastern marriage to be. The two are clearly equals, and married for love, not for any kind of personal gain. Their relationship is warm and sweet, as demonstrated by Raffo and Elouahabi’s frequent kisses and tendency to mindlessly gravitate towards one another on stage.

A theme that Raffo weaves into Noura through various characters and events is the difficulty of accepting one’s identity, particularly when one must reconcile the culture of their home country and that of the country they currently live in to do so. The principal way that the director, Joanna Settle, conveys this onstage, is by making Noura’s monologues moments in which the audience is taken inside her very mind. When Raffo begins a monologue, the lights dim, and the sounds of Middle-Eastern music and song echo on stage, accentuating the two mentalities that she is struggling to balance, the American and the Iraqi one. We also see an identity conflict in Tariq when he is deeply unsettled by Maryam’s pregnancy. He cannot come to terms with the fact that she is with child but unmarried, harshly wondering why she “couldn’t make it through college without opening her legs”. Tariq’s disgust stems from his having grown up in a country that places a prominent stigma on women’s sexuality.

I highly recommend Noura to everyone who is of middle school age or higher, simply because the more mature themes it includes could be confusing or uncomfortable to a younger audience. Additionally, It would be a very educational play for two people with different mindsets to go see together, such as a more liberal person and a more conservative one, or an adult and a teen, as it could provoke interesting conversations and debates.

Personally, seeing Noura was one of the best things that has happened to me in a while. It is an extremely powerful show that discusses issues that are both extremely relevant and controversial in our world today.