In the midst of the colossal Hollywood nightmare of cheesy rom-coms (think Bridget Jones’s Diary), ostentatious Oscar bait (The Revenant), gruesome horror movies (Rings), cash grab sequels (Furious 7), and plotless action fiascos (the entirety of the Marvel cinematic universe), rises director Wes Anderson: a messiah of unique, beautiful films.

A thoughtful, detail-oriented ingenue, Anderson has made his mark upon Hollywood with his gorgeous films. From the coming of age comedy ‘Rushmore’ that set Anderson on a course to greatness, to his most recent masterpiece “Moonrise Kingdom” that perfectly encapsulated the beauties of childhood. To call them ‘movies’ would be an understatement: his works aren’t simply for marketing, money, and entertainment like the Mission Impossible franchise; they are works of art.

His films are marked by a unique visual style and witty humour. They are often composed of flat space camera moves, symmetry, and deliberately limited color palettes; they are so aesthetically pleasing that I could watch some of his films without any volume.

In terms of humour and content, they are peppered with light, though cynical dialogue. His most recent film, the Grand Budapest Hotel (2014) is a culmination of all hallmarks that make Wes Anderson films so Wes Anderson.

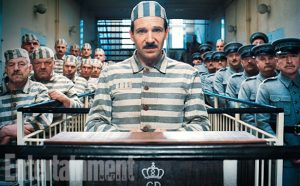

Set in the quaint fictional alpine town of Naplesbard, Zubrowka in 1932, the film centers around an eccentric hotel concierge M. Gustave (Ralph Fiennes in his funniest role) and his lobby boy Zero Moustafa (Tony Revolori). M. Gustave is wrongfully accused of murdering a very rich, old lover of his, resulting in his arrest, imprisonment and a subsequent quest to clear his name.

Though the plot is unoriginal, the film bursts with incredibly quirky and humorous moments that more than compensate for the lacking story. Perhaps that is the appeal: there is not a prominent central conflict, but rather central feelings of nostalgia and melancholy. Through each delicately crafted scene, wrapped and presented in a beautiful parcel, there is a deep undercurrent of sadness that pervades the picturesque sets.

Filled with soft pinks, cold blues, and the vivid compliments of orange and yellow, the Grand Budapest Hotel is a wonder of aesthetics. The near perfect symmetry of the camera angles, wide panels, and rotating cameras all but leave the viewer stunned.

However, the Grand Budapest Hotel is not merely a visual sensation; the film is also overflowing with wonderful dialogue. Anderson combines incredibly grandiloquent vocabulary and sentence structure with vulgarities in order to present truly humorous phases like: “I beat the living shit out of a sniveling little runt called Pinky Bandinski, who had the gall to question my virility. Because, if there’s one thing we’ve learned from penny dreadfuls, it’s that when you find yourself in a place like this, you must never be a candy ass.”

Perhaps what is so fantastic about the Grand Budapest Hotel, as with all Anderson’s movies, is that it presents contradictions. The universes Anderson so meticulously crafts are constrained to the characters, yet the struggles of those characters are infinite in relatability, from loss, to hope, to despair, to love. The characters are mostly vehicles to satisfy Anderson’s aesthetic desires, confined to dialogue and costumes that would be unusual in reality. Yet, his characters are also startlingly complex.

The greatest contradiction though, is the fact that while the movie presents beautiful scenes that are so aesthetically satisfying, they also leave the viewer starving for more delicate moments. That is the true genius of Wes Anderson: what he creates is so gorgeous, so enthralling, that no movie of his can truly be enough to satisfy the viewer.

by Erika Undeland