It’s been five years since the world first went on lockdown for the COVID-19 pandemic. On the surface, everything seems to be back to how it was before: the school halls are filled with students, the words “social-distancing,” “quarantine” and “cohort” are rarely used anymore and unopened packs of face masks are stowed, forgotten, in attic boxes. But those five years since 2020 have been far from easy, and damage to the WIS community hides beneath the surface.

In fact, the long-term effects of COVID have played a role in student performance, according to Upper School English teacher Katherine van Niekerk.

“We’re back to full force academically, but that transition back to full force has been difficult at times,” van Niekerk said. “The arc of moving into the full rush of academics post-COVID is sometimes noticeable. Sometimes you see blips where students might struggle to balance it all.”

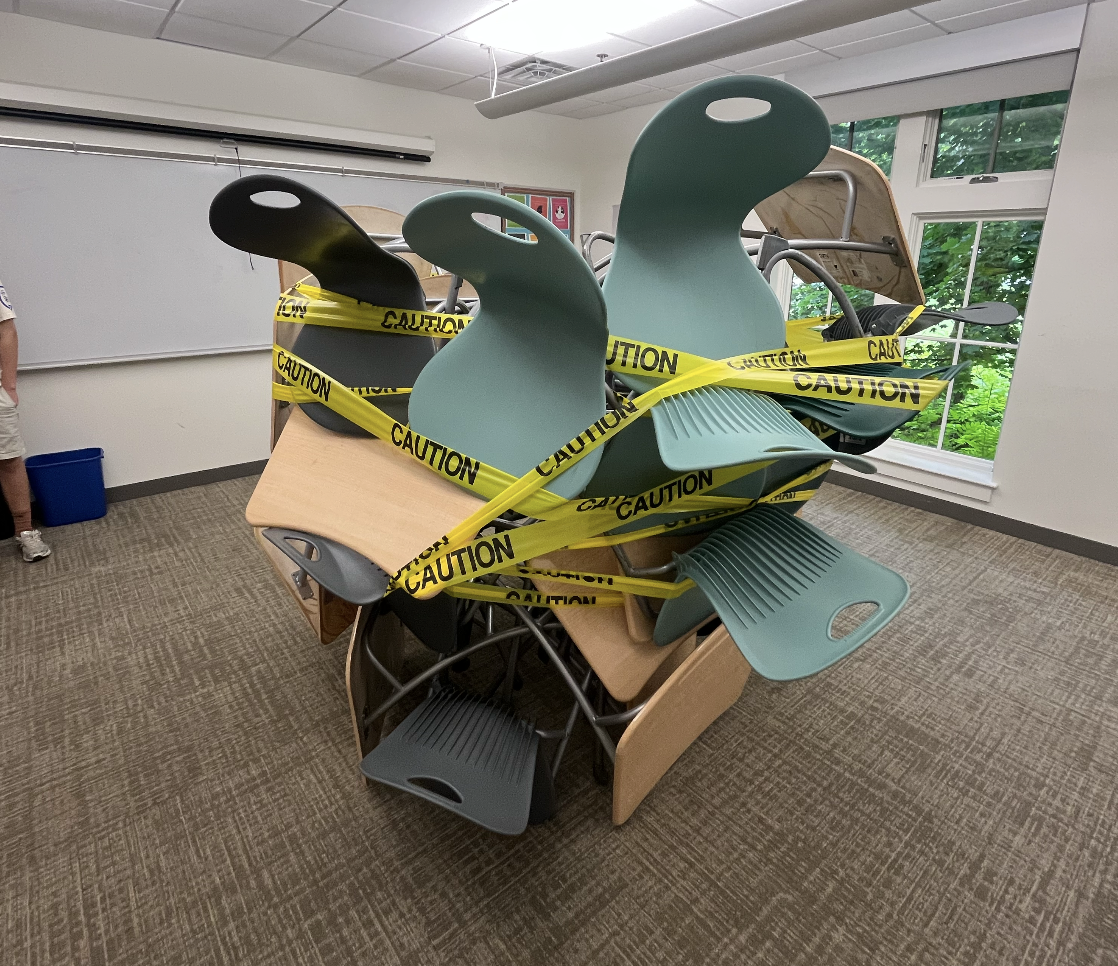

The science department has noticed one such blip; while school was virtual, the hands-on component of learning in the lab was missing. Upper School Biology teacher Sabrina Hoong remarks that this has had lasting effects on students.

“One of the big things lacking during COVID was labs,” Hoong saiPreview Changes (opens in a new tab)d. “Now I’m seeing a lower ability of lab skills in general.”

This concern is shared by others in the department. Because many current upper schoolers were in Middle School during the pandemic, the foundational lab skills that would typically have been taught then are now missing.

“In the science office, teachers talk about [students’] weak lab skills,” Hoong said. “They’re saying, ‘I’ve never had to teach this before. It used to get covered in middle school, but I guess because they didn’t do labs in middle school, it didn’t get covered.’”

Though these shortcomings start in the lab, they can extend to performance on tests and quizzes when necessary lab knowledge applies.

“Because some of the lab skills are missing, if there’s an exam question that’s more lab-based, students struggle more with that,” Hoong said.

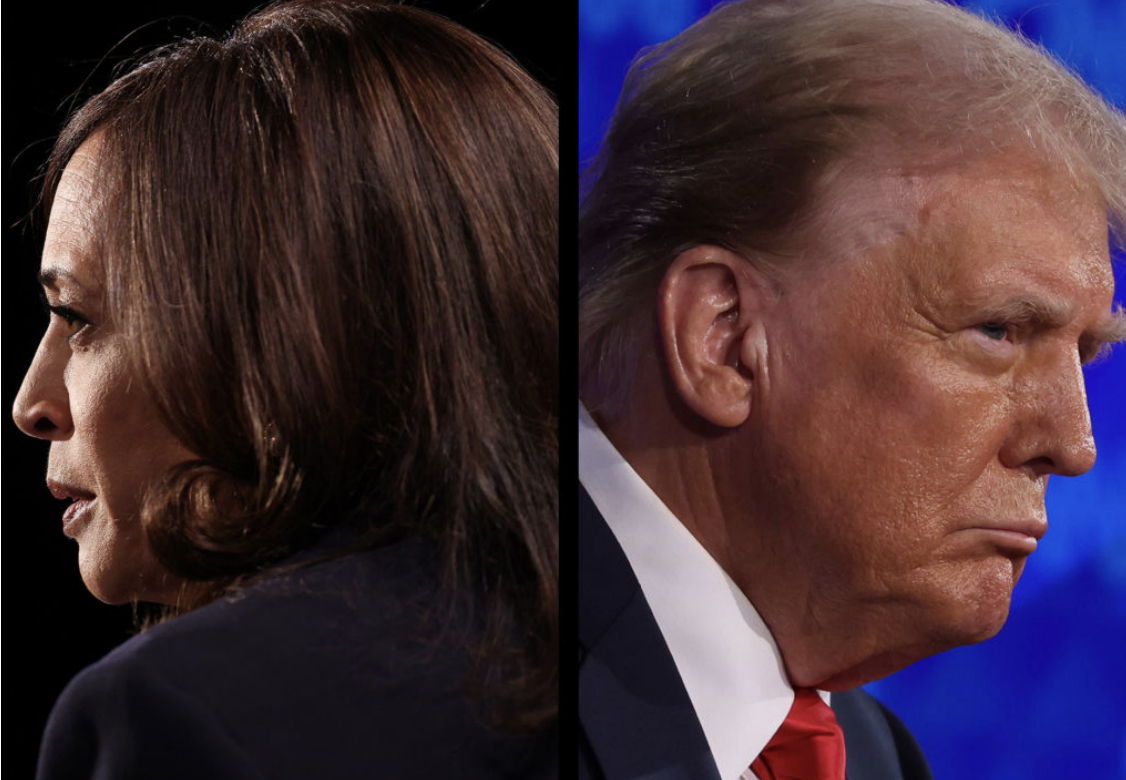

In an attempt to cover up the effects of diminished student performance during COVID, a grade boost was added to IB exams, according to college counselor Joanna Tudge.

“There was a do-no-harm of one additional point [on the IB exams] during COVID,” Tudge said. “That’s gone away now. It was definitely short and sweet.”

This policy was an attempt to support students during the difficult years of online learning. During that time, virtual school put a strain on both teaching and learning, which caused many teachers to try to compensate for the changes.

“Everybody struggled during COVID, but teachers didn’t show that to students,” van Niekerk said. “So we dug deep to try to prioritize them and try to leave behind whatever struggles we were dealing with.”

But prioritizing school was in no way easy for teachers when their classrooms were computers and their students were profile pictures.

“You’d be speaking into a void of black screens, with no cameras on,” Hoong said. “Like, is anyone there? Is anyone listening?”

There were, however, some silver linings to learning online. The separation of students helped with stress during the college process, Tudge believes.

“Students weren’t [at school] comparing, so they were very much on their own journey,” Tudge said. “They were just meeting online. There was less pressure from peers. They weren’t being judged, they didn’t have to share.”

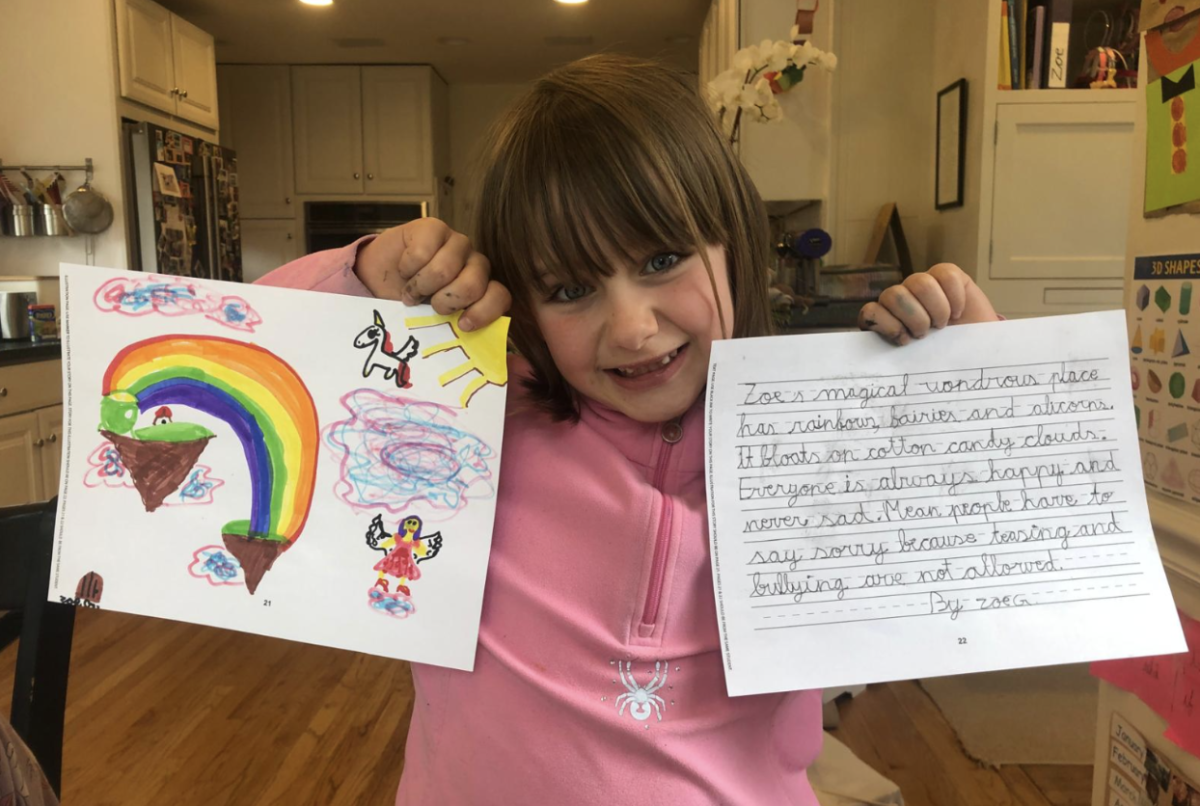

The positive aspects of virtual schooling also extend to extracurriculars. Some students, like junior Sophia Li, were able to do more of what they loved.

“Quarantine gave me different hobbies,” Li said. “During COVID, I realized I had so much free time that maybe I should just play music. I decided I would pick up piano, and then I might try going back to violin, and I might try guitar as well.”

The time spent at home also allowed some people to appreciate the joys of in-person school more; by the time school started again, many noticed aspects of school that had previously been taken for granted. Learning face-to-face was suddenly seen as a privilege, not a given.

“After [COVID], I cherished the in-person aspect a lot more,” Hoong said. “Just having the organic collaboration and conversations between students and teachers.”

In fact, some noticed that they were more sociable after the pandemic.

“COVID made me a bit more outgoing,” Li said. “I had to talk during Zooms. I was forced to. So afterwards, I got more comfortable with that.”

However, this sentiment is not shared by everyone. Many people believe that the years of virtual and hybrid school led to significant social setbacks in younger generations.

“In terms of their social skills, students now aren’t as comfortable having conversations,” Tudge said. “They’re not even comfortable even being on the phone with colleges. With their peers, there’s a bit of a disconnect.”

Junior Cecilia Howton notes that the increased use of technology during COVID changed the way people interact with one another, even today.

“It shifted how we talk to each other and how we communicate,” Howton said. “Everything shifted more online as we learned how to use online communication tools. I feel like I text my friends a lot more than I used to, or call them more than I used to.”

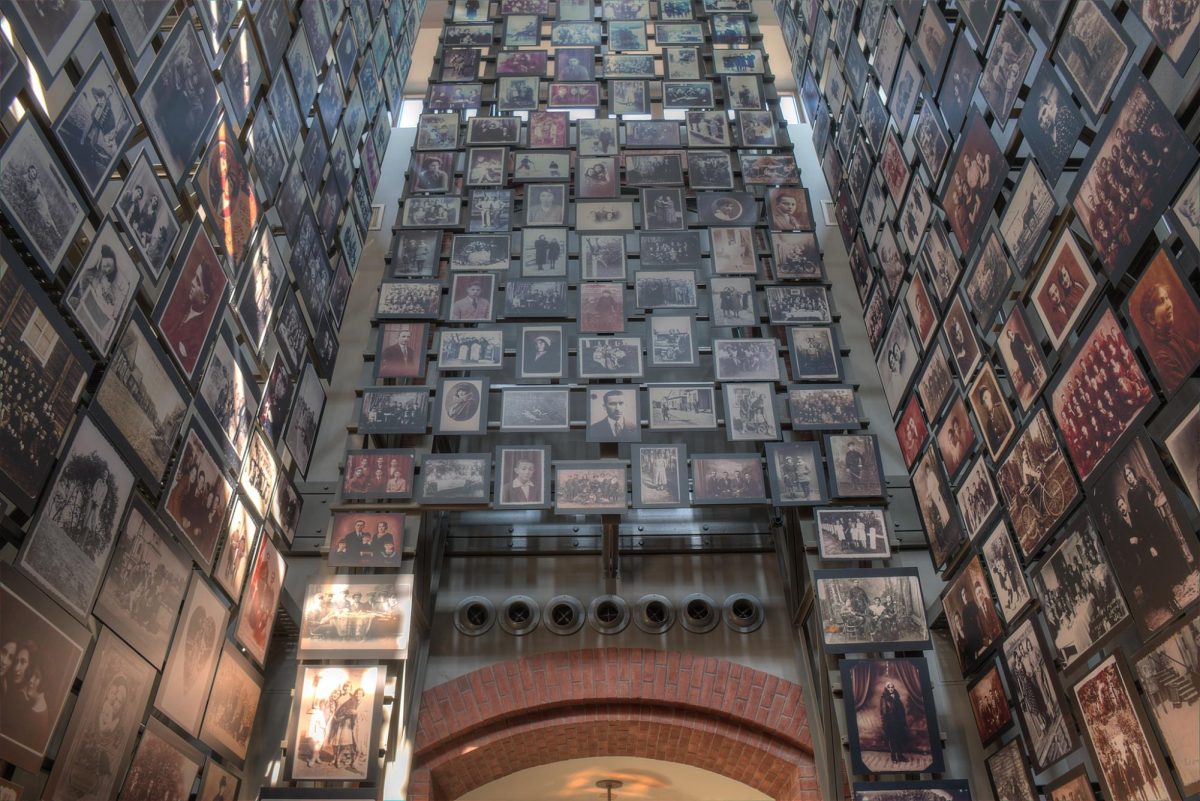

Despite the interconnectedness of online communication, the pandemic isolated people in their own homes and stripped away in-person interaction. This made it difficult to go back to normal after COVID.

“It was hard for students to find their people again,” Tudge said. “Some were really good at staying in touch, playing games online and having movie nights. Some students felt lonely.”

Because relationships during COVID were almost entirely online, those who didn’t find ways to interact with their friends online lost friendships.

“There were friends that I wasn’t able to keep in touch with during COVID,” Howton said.

The extent of COVID’s impact on the social world is impossible to know for sure. The one thing that is clear is that its consequences persist.

“Socio-emotionally, I think its effects will last,” Tudge said.

To combat these changes, teachers are more vigilant than ever to help fix the problems that might arise.

“I’m aware to have my radar up for mental health issues, more so than I ever have been in my career,” van Niekerk said. “And that’s a bump-on from COVID for sure.”

As well, teachers are trying to adapt their teaching style to ensure that students aren’t overwhelmed in the wake of COVID.

“Believe it or not, I’m more mindful of workload now, and how we as IB teachers pace that out,” van Niekerk said. “It’s always a challenge and a balance, but it’s something that I’m much more aware of because of synchronous and asynchronous classes.”

Despite the holes that COVID made in student education, teachers are constantly working to compensate for its impacts.

“Once we notice a gap somewhere that wasn’t filled in the past, we just adapt,” Hoong said. “We do what we do and step in and fill that gap.”

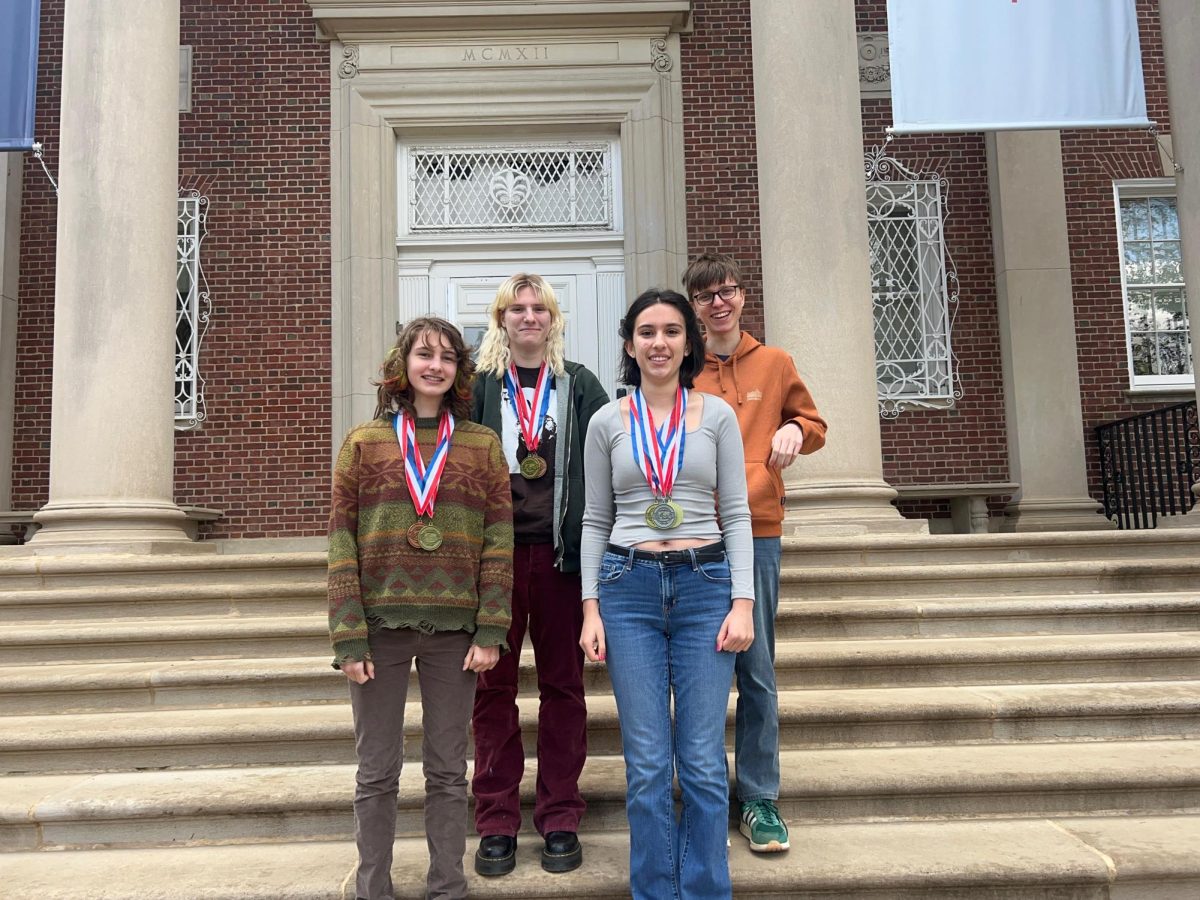

By Tindra Jemsby