June 30, 2023 will mark three years since the highly controversial National Security Law (NSL) was passed by the Standing Committee of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in Beijing and entered into force in Hong Kong (HK). The NSL has faced intense scrutiny and widespread criticism for its impact on free speech and civil liberties in HK since its implementation.

The law was introduced in response to widespread and often violent protests against the proposed extradition law in HK due to concerns about the protests’ potential implications for the city’s autonomy from mainland China, the rule of law and human rights.

Since the NSL was introduced, political institutions have been restructured and education and media reforms have been enacted. Critics say that the NSL has silenced political dissent and opposition voices by imposing limits on freedom of expression and of the press, but the HK government says the measures were necessary to address national security concerns and restore stability post-protests.

The proposed extradition law would have allowed individuals to be extradited from HK to mainland China to face trial under the Chinese legal system. This system is widely criticized for a lack of transparency and due process and an extremely high conviction rate of 99.9%. The proposal ignited mass protests from June 2019 until mid-2020.

The NSL’s consequences continue to shape the fabric of HK’s society and economy. Prominent media outlets with pro-democracy viewpoints have been raided, forced to shut down or had their assets frozen, notably Apple Daily and Stand News. These shutdowns have led to international accusations of press freedom violations from organizations such as Human Rights Watch and Reporters without Borders.

Meanwhile, daily life has changed, with citizens being more cautious of what they post on social media or discuss with colleagues and friends. Even so, the HK government claims the NSL does not affect the rights of law-abiding citizens granted under HK’s mini-constitution, the Basic Law, including freedom of expression and of the press.

“The vast majority of Hong Kong people who abide by the law and do not participate in acts or activities that undermine national security will not be affected [by the NSL],” the HK government said. “Life will go on as normal. The public will continue to enjoy the legitimate freedoms of speech, of the press, of assembly, of protest and procession, etc.”

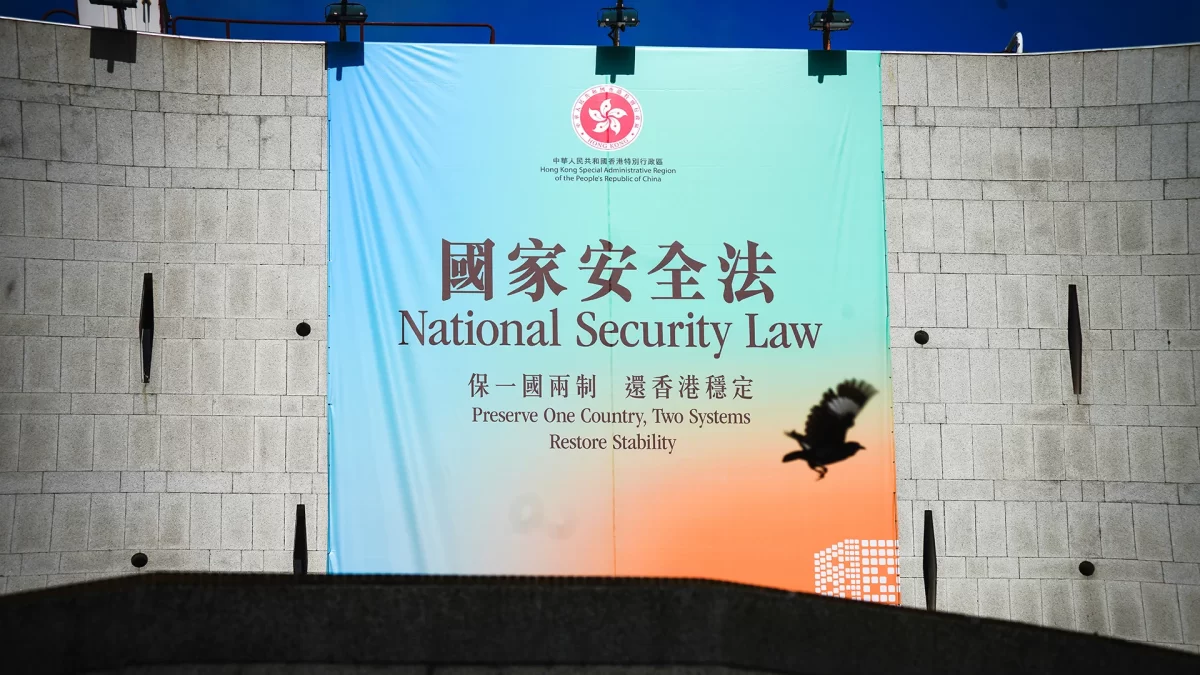

Tom Grundy, editor-in-chief of Hong Kong Free Press, an independent English-language newspaper based in the city, says that changes in HK’s society would initially be hard to spot for outsiders and tourists beyond billboards scattered around the city praising the NSL.

“You would not notice, really, for most people, especially tourists, that much has changed,” Grundy said. “But even day to day, regular people, they will certainly have to be thinking now about what they post on social media. They will certainly have had to have discussions at work, or their bosses or companies will have had to think about the National Security Law, and what that means for them, no matter what industry they’re in.”

In relation to the long-term effects of the NSL in the city, Grundy pointed to the onset of indirect censorship by the HK government and a lack of clarity and consistency about what is legal and illegal under the NSL.

“It became clear, through a series of court cases, that certain slogans became illegal in Hong Kong,” Grundy said. “[But it is not clear if] ‘Glory to Hong Kong,’ a popular pro-democracy anthem that was popularized during [the protests in] 2019… is illegal… People have been arrested who have sung that song in the street, but the government will point to other legal issues, such as COVID-19 group gathering violations.”

As of early April of this year, 250 people have been arrested under the NSL, a figure emphasized by HK’s Justice Secretary Paul Lam as being “only a very small number of people.”

Additionally, 20 to 30 individuals have been convicted under the law, and many have been high-profile figures. Critics say the arrests act as a warning message to the general population of HK, particularly the large number of people who took part in the 2019 protests.

These individuals include prominent pro-democracy activists such as Agnes Chow, Joshua Wong and most notably Jimmy Lai, a media mogul and founder of pro-democracy newspaper Apple Daily.

Lai has been charged under the NSL for allegedly “conspiring and colluding with foreign forces to endanger National Security” and charged with fraud and unlawful assembly in two other instances, according to AP News.

After a global fall in international trade and economic activity, HK is looking to revitalize its economy to retain its position as a major trading hub in Asia. The government says that the NSL will help achieve these goals.

“The National Security Law will add to the city’s institutional strengths and economic competitiveness as an international financial and business center,” the HK government said. “It will strengthen our stability, safety and security in the long run, which in turn will provide the certainty needed for business and investment to thrive.”

In relation to the NSL restoring stability to the region, a senior British official who was involved in the effort to respond to the NSL at the time and requested to remain anonymous remarked that perceived “stability” could be influenced by the threat of retribution from voicing dissatisfaction that the NSL brought about.

“[Stability] is a very difficult metric to measure, because as long as you lose your freedom of press and your freedom of speech… it’s not clear until it’s unstable where the pockets of disagreement and challenge exist,” they said. “It’s certainly true to say that there’s a higher level of fear, so the willingness of people to speak out is much diminished.”

The HK government presses on amid sustained criticism from nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), human rights groups and governments around the world.

“[The NSL] will protect Hong Kong from relevant threats, help maintain the city’s political and social stability as well as create a favorable environment in the long run for investments and conducting businesses,” the government said.

In response, foreign governments, particularly in the U.K. and the U.S., have condemned the law and its effects on freedom of expression and press.

“To suggest that our sovereign, China, does not have the right to legislate to protect national security in the [Hong Kong Special Administrative Region] (HKSAR) is not just wrong but also smacks of hypocrisy and double standards,” the HK government said.

However, the British official believes that the NSL was the last nail in the coffin for press freedom, freedom of expression and judicial independence in HK.

“Actions to close liberal media establishments in Hong Kong would never have happened before the NSL,” they said. “Whilst such intervention in the media landscape continues in Hong Kong, it’s not possible to say that Hong Kong has a free and open media, or anything like it.”

By Oliver Dashwood