A little girl of five years old splashes around in a public pool in the New Mexican summer heat. Someone asks her how she can swim and see through her eyes at the same time.

A twenty-year-old woman is walking down a street in New York. Someone yells at her to go back to her country. She’s terrified and crosses to the other side.

A woman of thirty carries pepper spray wherever she goes. Her family tells her not to take the metro to work; they’re scared that she could be attacked because she’s Asian.

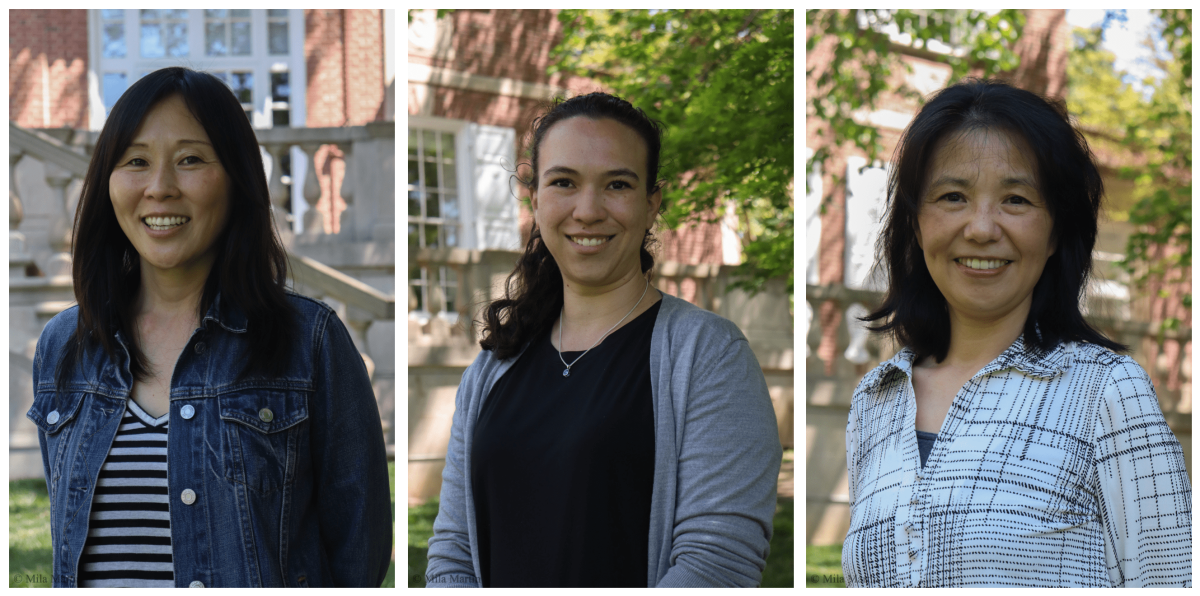

These three women are WIS faculty members Allison Ewing, Susan Chung Fontaine, and Hongli Holloman, respectively.

Assistant Principal for Grades 9 and 10 Allison Ewing’s mother’s family emigrated from China to the Hawaiian Islands. “My great-grandmother was sold as a slave by her family back in China to pay for her father’s funeral, and the family that bought her emigrated to Hawaii,” Ewing explained.

Upper School English teacher Susan Chung Fontaine’s parents were immigrants from Korea, and she grew up in New York.

Chinese teacher Hongli Holloman is fully Chinese and grew up in China. “I had my college education in China, [and] came to the United States after college. So I’ve been here for many years,” she explained.

The three women’s Asian heritage has often pushed them headfirst into the oncoming traffic of hateful Asian bigotry. “Even growing up, people – I’ll use the slurs – they called you, ‘ch**k’, ‘ch**g ch**g’, all of those types of slurs,” Chung Fontaine said.

And for many Asian women, these feelings of oppression and marginalization came to head after the Atlanta spa shooting that left six Asian women dead. “I was really sad. And then comes fear and the frustrations,” Holloman said.

Holloman adds that just being perceived as Asian can put her at risk. “When you hear people being attacked in the street, [when] they think they are Asian, or they think they are Chinese,” she said, “that adds a lot of psychological fear.”

This fear has forced Chung Fontaine and Holloman to take strong precautions. Both carry pepper spray on their person. “Every day, I actually have pepper spray attached to my keychain, it’s in my pocket,” Holloman said. “I don’t bring it out in school. But it travels with me.”

And it’s not just them. “Every Asian person I know is definitely more scared and paranoid just walking, being out in public,” Chung Fontaine said.

Ewing broadens this sentiment, applying it to all people of color. “Being a person of color, you’re automatically acutely aware of your surroundings and who’s around you, and how you can and can’t behave at certain times in certain ways,” she said.

While there has been some debate over whether this shooting is considered a hate crime, Ewing, Chung Fontaine, and Holloman are all in agreement. “My first thought was that it was a hate crime. And that has now culminated in a massacre,” Chung Fontaine said.

Sophomore Zachary Pan agrees. “There are news sources that have not called it a hate crime, even though, if like 90%of the victims are Asian Americans when Asian Americans are 5%of the population, that’s kind of a telling sign that it really is a hate crime,” Pan said.

Pan’s mother is Chinese-American. His parents fled from China after siding with the Nationalists, who lost in their civil war against the Communist Party. “They had to flee to Taiwan and that was the last bastion of democracy in China,” he said.

Chung Fontaine, Pan, and Holloman all note that former president Donald Trump’s statements about the “China virus” and the “Kung Flu” had a significant impact on the rise of Asian hate crimes. “I think it’s giving a green light to people who have that prejudice and bias to just act out on it,” Chung Fontaine said.

Ewing adds that one of her friends took these statements to heart. “She decided that she wasn’t going to be the one to go to the grocery store, especially when the pandemic first set and people were saying things about Asians and the coronavirus,” she explained.

IB Math teacher Eugene Wang, Chinese, experienced first-hand the impact of this negative rhetoric when he was traveling. “People were pointing fingers or just intentionally walking away or name-calling,” he said. “Or the worst thing that happened was people spitting on you.”

However, Wang acknowledges that there’s a distinct difference between the racism that Asian men and women face, especially in the media. “Asian females are being sexualized more and more…and on the other hand, you look at the Asian male [who’s been] emasculated,” he said.

The sexualization and fetishization of Asian women stem from colonization. “White sexual imperialism, through rape and war, created the hyper-sexualized stereotype of the Asian woman,” according to author Sunny Woan.

This sexualization continues to have a large impact on Asian women today. “When you grow up in a racist society, you’re not conscious and aware that these ideas permeate your mind, or they did mine,” Chung Fontaine said. “And so as an adult, I’ve worked to sort of free myself from those ideas, but I think it’s still a process.”

Additionally, the alleged motive of the Atlanta mass shooter was an inability to control his sex addiction, which he was previously treated for. Many believe that the motive of the crime was strongly connected to the sexualization of Asian women.

Similarly, the depiction of Asian men in movies and TV shows had a large effect on Wang when he was a teenager. “One of the struggles growing up as an Asian in America is you don’t see role models,” Wang explained. “You just rarely see them anywhere in sports, politics, or science, entertainment, [it’s] very rare besides a few stereotypical martial arts actors.”

He believes that the difference between the depiction of Asian men and women in media stems from the white male point of view.

Wang explains that from this point of view, Asian women are in some ways more welcome in America because they bring “benefits” for white men. “[Asian men] are potentially competitors to the white male-dominated culture, so they are being emasculated to be portrayed as shy and weak,” he said.

Plus, media portrayal extends beyond fiction, into the coverage of hate crimes. “[If] you read about these crimes, the word being used to describe this group of people is always Asian-Americans,” Wang said. “As if this person is not an American passport holder or a non-American citizen, this person does not qualify for the protection of the law and the constitution.”

But no matter how you slice it, there’s discrimination from every angle. “It’s unfair either way,” Wang said.

Though exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, anti-Asian racism is not a new phenomenon, with roots in immigration and legislation since the 19th century, according to the Washington Post.

The Rock Springs Massacre of 1885, which killed 28 Chinese immigrants, combined with the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 that banned Chinese immigration for 80 years, resulted in the creation of Chinatowns, Asian communities within white-dominated towns intended to protect the marginalized group.

Washington D.C.’s Chinatown, a small section east of downtown D.C., has experienced increasing gentrification within the last 30 years, as authentic Asian-owned businesses continue to close down.

There is a clear connection between the history of anti-Asian racism and events occurring today. “Whenever there’s a crisis or a scenario where there is pain or economic suffering, people look for a scapegoat, and I think Trump directed that at Asian-Americans in an effort to win reelection,” Pan said.

This continuous discrimination against Asian-Americans has made it difficult for Wang and Chung Fontaine to retain and show off their cultures.

Growing up, Wang felt like there were only two cultures represented in America, white and Black, with no room in between for his Chinese identity. “There’s only a group of people you can share these cultural values [with] and the tendency for immigrant children [growing up] in America is to try to be assimilated into the American mainstream culture,” Wang said.

Consequently, Chung Fontaine doesn’t express her Korean culture very much. “I don’t think I wear it on my sleeve,” she said.

While these Asian-Americans face discrimination almost everywhere, WIS can be a safe haven for some of them. “WIS has been really incredible in terms of being welcoming, and engaging in dialogue,” Ewing said.

However, Chung Fontaine feels slightly differently, acknowledging that WIS doesn’t have a lot of Asian diversity, with Asian students making up 2 percent of the student body. “I definitely feel safe. But I’m aware of being one of the few,” she said.

But despite these differences, all four faculty members have similar goals and hopes for the future of America and its anti-Asian racism. “I want it to be less prejudiced, less biased, less racist, I want justice for people who’ve done wrong, I want accountability for people who act on their hate,” Chung Fontaine said.

She adds how allies of the Asian community can help and support. “When there is injustice, to stand, to be vocal and stand with those who are victimized [and] persecuted,” Chung Fontaine said.

However, Holloman highlights the recent Asian hate crimes’ one silver lining. She characterizes the recent increase in media coverage as “attention being paid to the so often ignored.”